Key takeaways

- Digital asset custody involves the safeguarding of the private keys corresponding to a digital asset. Whilst an owner can self-custody his digital asset, third-party custody is growing dramatically. One reason is the preference of owners to involve experienced intermediaries to safeguard their keys (and thereby bear some burden in case the keys are lost). Another reason is regulatory – certain institutional investors are obliged to use accredited custodians to safeguard their assets.

- The digital asset custodial industry has a broad array of players, including direct custodians, Custodial technology services providers and hybrid service providers.

- As with traditional custody, digital asset custody is in practice provided either on a title transfer basis or through a trust arrangement. It is not unusual for a custodian’s documentation to be unclear regarding the nature of the custodial relationship. In the event of a dispute, English courts will likely look at the contractual terms as well as how the digital assets were held in practice. Other complicating issues are the segregation model (whether individual or omnibus), the use of sub-custodians and any contractual liability limitations.

- The EU’s regulatory framework is already established under the Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCAR) and the direction of travel in the UK is becoming clearer.

- Under MiCAR, there is a heavy emphasis on ensuring effective segregation and, given its central importance in the provision of custody services, the UK regime is likely to follow suit.

- As is the case with providers of traditional custodial services, MiCAR imposes organisational, conduct and prudential requirements on digital asset custodians and the FCA is expected to do the same.

1. Summary

1.1 As the old adage, often misquoted and misunderstood, goes: “possession is nine-tenths of the law”.

Leaving aside exceptions such as theft, fraud or mistake, there is an innate logic to ownership of an asset being derived from physical possession. English common law supports this view; ownership of an asset is best ascertained by identifying the person who exercises “control” over it. This control should ideally be both positive (e.g., having exclusive use of the asset) and negative (e.g., denying others from enjoying the asset).

1.2 Nevertheless, over the course of time, human societies have worked hard to concoct arrangements that split ownership for a variety of reasons. An asset can be owned by multiple individuals. It is also possible for a person to hold an asset on behalf of someone else. That is, one person can be a legal owner and an entirely different person can be the beneficial owner.

There are innumerable examples. Before setting out to join a crusade, a knight passes ownership of his lands to his brother for safekeeping and expects them to be given back to him upon his return. A child inherits a hotel chain from their doting aunt and the court appoints a trustee to run the operations until the minor comes of age. School teachers pool their savings into a mutual fund that is overseen by a professional money manager who decides which securities to buy and when to sell them. A couple give legal title over their new home to the bank that has given them a loan to purchase it. And so on and so forth.

1.3 In financial markets operating in common law jurisdictions, ownership is often splintered by the use of a trust (or a contractual or statutory arrangement that operates similarly to a trust). An intermediary such as a custodian or a depositary holds and safekeeps the financial asset such as a bond, share or derivative on behalf of investors. As the intermediary exercises factual control over the asset, legal ownership resides with it, but with the investors having beneficial rights to the asset. Should the intermediary fail in its duties for any reason, the investors rely upon principles such as bankruptcy remoteness and segregation to protect their beneficial ownership (that is, the property rights) over the asset.

Bond issuances are instructive. Bonds can be issued in either bearer or registered form. In the former case, the bond was historically represented by a physical (typically paper) instrument. The person – the bondholder – possessing this instrument was entitled to interest and principal. They could sell the bond by giving the instrument to another person. Since the 1990s bearer bonds have been progressively dematerialised. This means that the physical instrument is held by a custodian. Investors participate in the bond indirectly by acquiring and trading rights against the custodian through a chain of intermediaries, with their entitlements represented in book-entry records and any transfers represented by way of book entries.

1.4 As the reader is well aware, digital assets continue to grow as a financial asset class. Not all investors want to hold (or are capable of holding) digital assets themselves and would prefer others to do so on their behalf. This raises the question as to whether intermediaries can legally hold digital assets on behalf of others. Even if the answer is yes (and it is yes at least as far as English law is concerned), this then gives rise to further questions as to how intermediaries can do so, given that digital assets are data and often held on distributed ledgers, there are risks emanating from intermediary default and the legal landscape is rapidly evolving.

This client alert discusses the following:

(a) whether an investor has contractual or proprietary claims following the default of its intermediary;

(b) whether a trust can be used to construct an intermediary relationship for holding digital assets;

(c) the differences between omnibus and individual segregation, and the attendant risks and benefits of each model; and

(d) the regulatory approaches in the EU and UK in regulating digital asset intermediaries.

2. The building blocks of digital asset custody

“Not your keys, not your coins”

2.1 When owners talk about having custodied their digital assets, what they usually mean is that their private keys are held with an intermediary.

Keys are generated through the use of a string of very long and random cryptographic characters, which make them nearly impervious to replication. The public key is derived from the private key. The former is the address to which people send transactions and, indeed, any transaction can be traced to it. The latter allows owners to initiate and authenticate their own transactions in order to access the digital asset they have stored in their wallet on distributed ledger technology (DLT).

The owner’s wallet contains both their public and private keys and has a wallet address linked to it. It is common for the wallet address to be a cryptographically hashed version of the public key, thereby making it easier to send digital assets to and from it. A digital wallet, therefore, is not dissimilar from an actual wallet which stores objects (e.g., cash, debit and credit cards, and store cards) and so allows a person to engage in transactions.

Wallets fall into one of the following three general categories:

(a) Hot. A hot wallet is always connected to the internet. Whilst this makes the wallet easily accessible and so helps in permitting transactions to be executed efficiently, it also inevitably increases security threats such as hacking or phishing attacks.

(b) Cold. A cold wallet (also known as a hardware wallet) is a physical storage device such as a hard disk or a USB stick and so not connected to the internet. Whilst this lowers security threats, it necessarily slows down trade execution.

(c) Warm. A warm wallet is a hybrid between hot and cold wallets. It is not continually connected to the internet but can be connected when needed. It provides a greater level of security than a hot wallet since it stores private keys offline. However, it is less convenient since it requires manual intervention in order for it to be brought online.

No wallet is immune from security threats. If an owner loses their keys, they are likely to lose the corresponding digital asset. This is especially so given the pseudonymous nature of digital assets, which makes the tracing techniques used to recover traditional financial instruments far more difficult. In this regard, digital assets are very similar to traditional bearer bonds.

All this means that the management of private keys is vitally important.

Private key management

2.2 Keys can be managed in the following two ways:

(a) Self (or direct) custody. Owners themselves hold and are responsible for the safekeeping of their private keys. Whilst this gives the owner direct control over their digital asset, it also means they bear the attendant risks. If the owner loses access to their wallet or forgets their private keys, their digital asset will be most likely lost forever.

Where the digital assets are held on a pooled basis, self-custody is impracticable. Furthermore, certain investor classes are mandated to appoint custodians. For instance, in the context of most fund vehicles (whether the fund vehicle itself is subject to regulation or not), a depositary is required to ensure that investors’ entitlement to their interests in the fund is properly recorded. The use of digital assets in connection with pooled investment vehicles, both to hold the underlying property of the fund and to record the interests of investors in the fund, is expected to become widespread.

(b) Third-party custody. The owner gives their private keys to a third-party intermediary for safekeeping. For practical reasons, it is usual for the intermediary to transfer the assets to its own name and so generate new keys.

Third-party custody of digital assets has been growing in leaps and bounds. According to a report by Blockdata, the size of digital assets under custody jumped sevenfold between 2019 and 2022, from US$32 billion to US$223 billion.

Entities are offering different sorts of custody services. Indeed, some of these services are not custody in the traditional sense but services such as “sharding” keys so they are held by multiple individuals for additional security. Such custody-like services can still result in some form of control (positive and/or negative) being exerted over the digital asset. The blurring of lines between traditional custody services and custody-like services creates challenges for UK regulators when considering where to establish the regulatory perimeter.

Third-party digital asset custody can be divided into one of the following three categories:

(i) Direct custodians. These entities play a role familiar to traditional custodians in that they exercise factual control (both positive and negative) over digital assets. They include traditional custodial banks, exchanges and digital asset managers.

(ii) Custodial technology services providers. These entities provide software and/or hardware devices to owners of digital assets to undertake self-custody more securely. They do not exercise positive control (which resides with the owner) but they can potentially exercise negative control. For example, an error in the programming of a wallet provider could result in the private keys being accidentally deleted or being transferred to another person.

(iii) Hybrid service providers. Hybrid service providers include entities that provide both direct custody services and, separately, other technology services. This captures entities that provide “multi-signature” (or multi-sig) services. A shared custody service is created due to the private key comprising different “shards” and different shards being capable of being shared by the owner and the service provider. The service provider is not capable of exercising unilateral positive control, but it can potentially exercise negative control by, say, losing its part, or shard, of the private key.

3. Determining the nature of the investor’s claims against its intermediary

3.1 Last year saw the high-profile failures of digital asset exchanges and lending platforms such as BlockFi, Celsius Network, FTX and Voyager Digital. FTX’s failure has raised vexing questions regarding conflicts of interest, market conduct and operational resilience. It has also demonstrated that integrated business models – currently prevalent across the ecosystem – can result in complex and sometimes self-reinforcing risk profiles.

Unsurprisingly, insolvency risk is receiving special attention. Were an intermediary to fail, the investor would understandably expect to extract its digital assets from the insolvent estate (subject to first discharging any outstanding liabilities owed to the intermediary and other parties). However, under English law, this ability depends on whether the investor’s relationship with its intermediary functions on a title transfer (i.e., a debtor-creditor) or proprietary basis.

3.2 In the former case, the term “custody” is a misnomer as all property rights (that is, legal and beneficial title) over the digital assets are transferred by the investor to the intermediary against a contractual obligation for the intermediary to deliver equivalent digital assets to the investor. Should the intermediary fail, the investor can only claim against the intermediary for breach of this contractual obligation owed to the investor. If the investor has not been granted security over its digital assets, the investor will rank as an unsecured creditor in the insolvent estate.

In the latter case, where the investor has a proprietary claim, the intermediary acts as the investor’s trustee. Since the investor’s digital assets should have been ring-fenced from the intermediary’s assets (and, where individual segregation applies, from the assets of other investors), the investor should be able to exercise its beneficial rights and have the keys transferred to it. In other words, the investor’s keys should be “bankruptcy (or insolvency) remote”.

The key difference, therefore, between the two intermediary relationships is whether the investor has a contractual or a proprietary claim against the intermediary in respect of the digital asset.

3.3 Although a trust is clearly more beneficial, title transfer arrangements are significantly more commonplace. Such arrangements tend to be cheaper for investors due to the intermediary being given the flexibility to use the digital assets for its own purposes (e.g., by generating revenue through transaction and DLT validation activities or selling the digital assets to third parties) whilst only having an obligation to transfer the keys of equivalent digital assets to the investor at contractually pre-agreed times. In fact, title transfer arrangements may well be a necessity if the intermediary also offers market-making or prime brokerage services which require it to have full title over the digital assets.

3.4 The following issues further affect the investor’s claims against the intermediary:

(a) Segregation. Whether the intermediary has in fact segregated the digital assets and, if so, whether such segregation is on an omnibus or individual basis. Where it is the latter, the investor is exposed to shortfalls in the holdings of other investors with which it shares an omnibus account (please see paragraph 5.1 below);

(b) Sub-custodians. Whether the intermediary uses other parties (sometimes referred to as sub-custodians) to either hold or manage the keys of digital assets. As discussed above, hybrid service providers are commonplace and even direct intermediaries routinely use the services of specialist entities such as wallet or multi-sig service providers. If a sub-custodian were to lose the private keys, then clearly this would impinge upon the intermediary’s ability to return them to the investor. This is especially so if the intermediary only has a contractual (rather than a proprietary) claim of its own against the sub-custodian. In such circumstances, the investor’s proprietary claim against the intermediary would be significantly weakened in practice; and

(c) Liability limitations. Whether the intermediary’s liability has been contractually limited or capped. Whilst there are certain liabilities which an intermediary cannot contract out of (e.g. losses resulting from the intermediary’s fraud), there are many others which can be watered down (e.g., losses resulting from sub-custodian default or losses resulting from hacking).

3.5 It is not unusual for the intermediary documentation to be unclear or even contradictory regarding the nature of the intermediary relationship. If a dispute between the parties arises (and assuming that English law governs the relationship), it is a matter of construction as to whether the investor has a proprietary or contractual claim against the intermediary in respect of the digital assets. Unsurprisingly, in a recent paper (the “ISDA Digital Assets Bankruptcy Risks Whitepaper”), the International Swaps and Derivatives Association, Inc. (ISDA) recommended that parties establish at the outset the key aspects of the intermediary relationship such as its governing law, the nature of the investor’s claim, whether and how sub-custodians will be used and the sort of segregation being offered.1

The digital assets working group of the International Institute for the Unification of Private Law (UNIDROIT) in fact has recommended that an intermediary relationship should be presumed to be based on custody (in the sense of a trust) where an intermediary holds digital assets on behalf of investors, unless the contractual terms specifically contemplate title transfer (or another type of similar arrangement).2 While the Law Commission’s consultation paper on digital assets (the “Law Commission Digital Assets Consultation Paper”) sees merit in UNIDROIT’s suggestion, the Law Commission has hesitated from recommending a law change to accommodate it due, in part, to the desire to safeguard the diversity of custody and custody-like services that the digital asset industry offers to customers.3

4. Applying a trust to intermediary relationships

4.1 A trust relationship provides a key benefit to an investor; namely, the keys of its digital asset are bankruptcy remote. Furthermore, being trustees, intermediaries are subject to certain irreducible obligations, including a duty of care on the trustee.

The value of these benefits naturally raises the question as to whether intermediary relationships over digital assets can be treated as trusts.

4.2 Thankfully, there is an emerging consensus within the legal industry that English law recognises digital assets as being the subject-matter of property rights and so capable of being held on trust.4

4.3 The Law Commission Digital Assets Consultation Paper summarises the following “three certainties” necessary for creating a trust under English law:

“(1) a clear intention by the relevant party or parties for the custodian to hold its title to specified crypto-token entitlements on trust for one or more beneficiaries (and resulting in the grant of equitable property claims in such entitlements to those beneficiaries);

(2) sufficient identification of the beneficiaries that are the objects of the trust; and

(3) sufficient identification of the crypto-token entitlements constituting the property interests that will be the subject matter of the trust.”

The Law Commission’s assessment is that digital asset intermediary relationships can satisfy these requirements. In particular, the Law Commission has analysed Ruscoe v. Cryptopia5 where the New Zealand High Court recognised the existence of a series of trusts over digital assets held in connection with customer trading accounts (and to a limited extent the intermediary’s own trading activity) at the Cryptopia exchange. The court was satisfied that the first of the “three certainties” (i.e., certainty of intention) was established by a combination of factors, including the structure and content of the internal database maintained by Cryptopia to track client account balances, as well as the fact that Cryptopia did not intend to, and in fact never did, use digital assets held on behalf of and in support of its customers’ trading balances to engage in trading for its own account. This judgment can be contrasted with Quonine Pte Ltd v. B2C2,6 where the Singapore Court of Appeal did not recognise a trust structure in connection with customer account balances held at the Quonine exchange for a variety of reasons, including Quonine’s market-making activities, the lack of sufficient digital tokens being actually segregated and the exchange’s risk disclosures, which expressly warned its customers of the substantial losses they could suffer if Quonine became insolvent.

As is demonstrated by these judgments, whether a particular arrangement with an intermediary is considered a trust depends not just on contractual terms governing that arrangement but also how it functions in practice. This only highlights the importance for investors to conduct wide-ranging due diligence before entering into a relationship with an intermediary.

5. Segregation

5.1 Where an arrangement with an intermediary is intended to operate as a trust, the intermediary ought to segregate the investor’s digital assets. Broadly, there are two segregation models:

(a) Individual segregation. The investor’s digital assets are segregated not only from the assets of the intermediary (i.e., house assets) but also the assets of other investors; and

(b) Omnibus segregation. The investor’s digital assets are segregated from house assets but pooled with the assets of other investors (or a sub-set of them). Given the additional complexities arising by virtue of individual segregation, it is typically a more expensive model than omnibus segregation. On the other hand, it offers the investor greater protection as it is not subject to the risk of shortfall.

If done properly, segregation using either of these two models should occur not just at the level of the intermediary’s books and records but also within the intermediary’s wallet.

In other words, where an investor has opted for individual segregation, the intermediary’s books and records should identify certain digital tokens attributable to the investor. To replicate the book-entry records, there should be a wallet on the relevant DLT in the intermediary’s name but recognising the investor’s beneficial entitlement to the assets held within it.

Where an investor has opted for omnibus segregation alongside a certain class of other investors, the intermediary’s books and records should identify certain digital tokens attributable to such class of investors, as well as each investor’s entitlement to the particular assets that investor owns. There should also be a wallet on the relevant DLT in the intermediary’s name but holding all the assets attributable to the class of investors. In the event that there are more claims by investors than the number or value of digital assets held in the wallet (e.g., due to the wallet being hacked and certain digital assets being lost), then any shortfalls will be shared between the relevant class of investors, typically on a pro rata basis.

6. The UK’s and EU’s regulatory trajectory

NB In this section, we have referred to digital assets as “crypto-assets” as this is the terminology used in MiCAR and the HMT Consultation.

EU’s regulatory approach - MiCAR

6.1 In May 2023, the European Union passed the Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation7 (“MiCAR”) into law. MiCAR introduces a new regulatory framework for regulating the European crypto-asset industry. The regulation aims to protect consumers and investors and to mitigate risks to financial stability by, among other measures, requiring that crypto-asset service providers (“CASPs”) obtain authorisation in order to operate within the EU.

6.2 CASPs are entities which engage in services or activities pertaining to crypto-assets, including the operation of a crypto-asset trading platform, the execution of orders for crypto-assets on behalf of clients, and receiving and transmitting orders for crypto-assets on behalf of clients. CASPs also include entities which provide custody and administration of crypto-assets on behalf of clients.

The scope of these services betrays the umbilical cord linking MiCAR to MiFID II. In spite of these strong similarities, it is important to note that MiFID II recognises the custody of financial instruments as an “ancillary service” only. The fact that MiCAR recognises this service as a stand-alone service requiring authorisation in its own right emphasises the central importance of custody to the growth of the crypto-assets market. At the same time, MiCAR has clarified that security tokens that fall within the definition of MiFID II “financial instruments” (e.g., digital bonds and digital shares) will continue to be regulated by that directive.

6.3 At a high level, intermediaries that are CASPs will be subject to organisational, conduct and prudential requirements.

They will have to satisfy requirements in relation to governance and have clear policies regarding the safeguarding of funds, business continuity, complaints handling, management of conflicts of interest and outsourcing.

6.4 Unsurprisingly, segregation requirements feature heavily in MiCAR for those intermediaries offering custody services. Ownership of crypto-assets held by the custodian must be clear from a legal perspective, with those crypto-assets belonging to clients being legally distinct from those belonging to the custodian. From an operational perspective too, crypto-assets belonging to clients must be held separately from the custodian’s own assets to protect against creditor claims in the event of the intermediary’s insolvency. On the DLT, this separation must be clear. Despite these high level requirements, the application of these rules in EU member states is likely to vary.

6.5 Furthermore, MiCAR provides that a custodian is liable for the loss of client crypto-assets or the means for clients to access those assets (i.e., via their private keys) where such losses are caused by an event or incident within the custodian’s control. Where a client suffers loss due a wallet being hacked, the intermediary will only avoid liability if it can demonstrate that its security measures and business continuity plans were of a reasonable standard and consistently maintained. MiCAR caps the intermediary’s liability to the market value of the relevant crypto-assets that are lost.

6.6 From a conduct perspective, intermediaries will be required to:

(a) act honestly, fairly and professionally in accordance with the best interests of their clients and prospective clients;

(b) provide information that is fair, clear and not misleading, with marketing communications clearly identified;

(c) communicate clear warnings regarding risks associated with transactions in crypto-assets; and

(d) meet prudential requirements, including holding certain amounts of capital in the form of either own funds or an insurance policy.

UK’s regulatory approach

6.7 The development of the UK’s approach to the regulation of digital assets is behind various other jurisdictions such as the EU, Singapore and Switzerland that have already passed into law foundational legislation, or will do so in the near future.

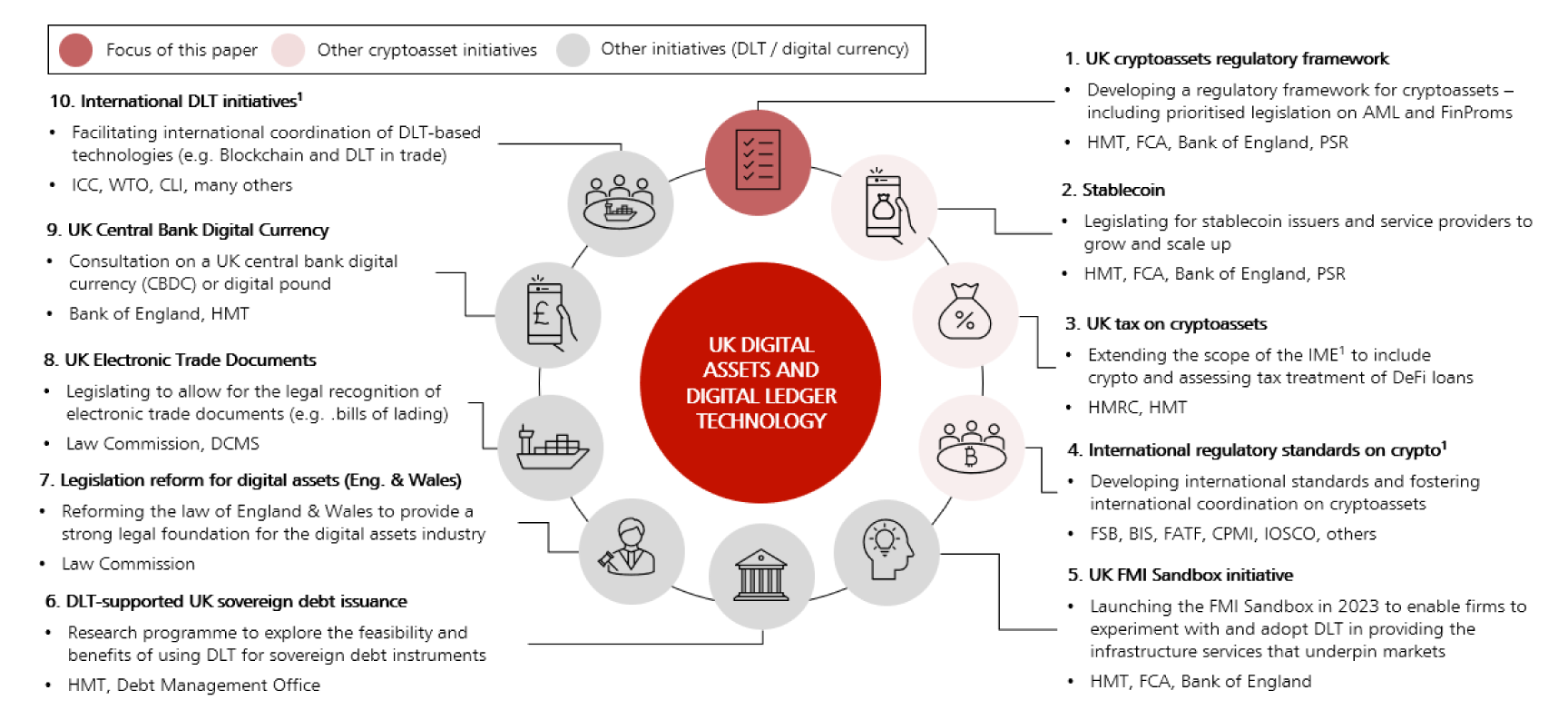

Furthermore, the UK’s regulatory approach is somewhat fragmented as various initiatives are being run by different regulators.

Source: HMT Consultation

6.8 In October 2023, His Majesty’s Treasury (HMT) provided its response to a consultation which it had conducted entitled “Future financial services regulatory regime for cryptoassets” (the “HMT Consultation”). The HMT Consultation provides helpful insight into the way the UK framework is likely to develop.

HMT proposes to regulate crypto-assets under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (“FSMA”), as amended by the Financial Services and Markets Act 2023 ( “FSMA 2023”). HMT will then be able to specify crypto-asset activities within the existing framework of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Regulated Activities) Order 2001 ("RAO”), or to designate them as part of the Designated Activities Regime (“DAR”). When such activities are carried out in relation to relevant crypto-assets, the intermediary carrying them out will be subject to regulation.

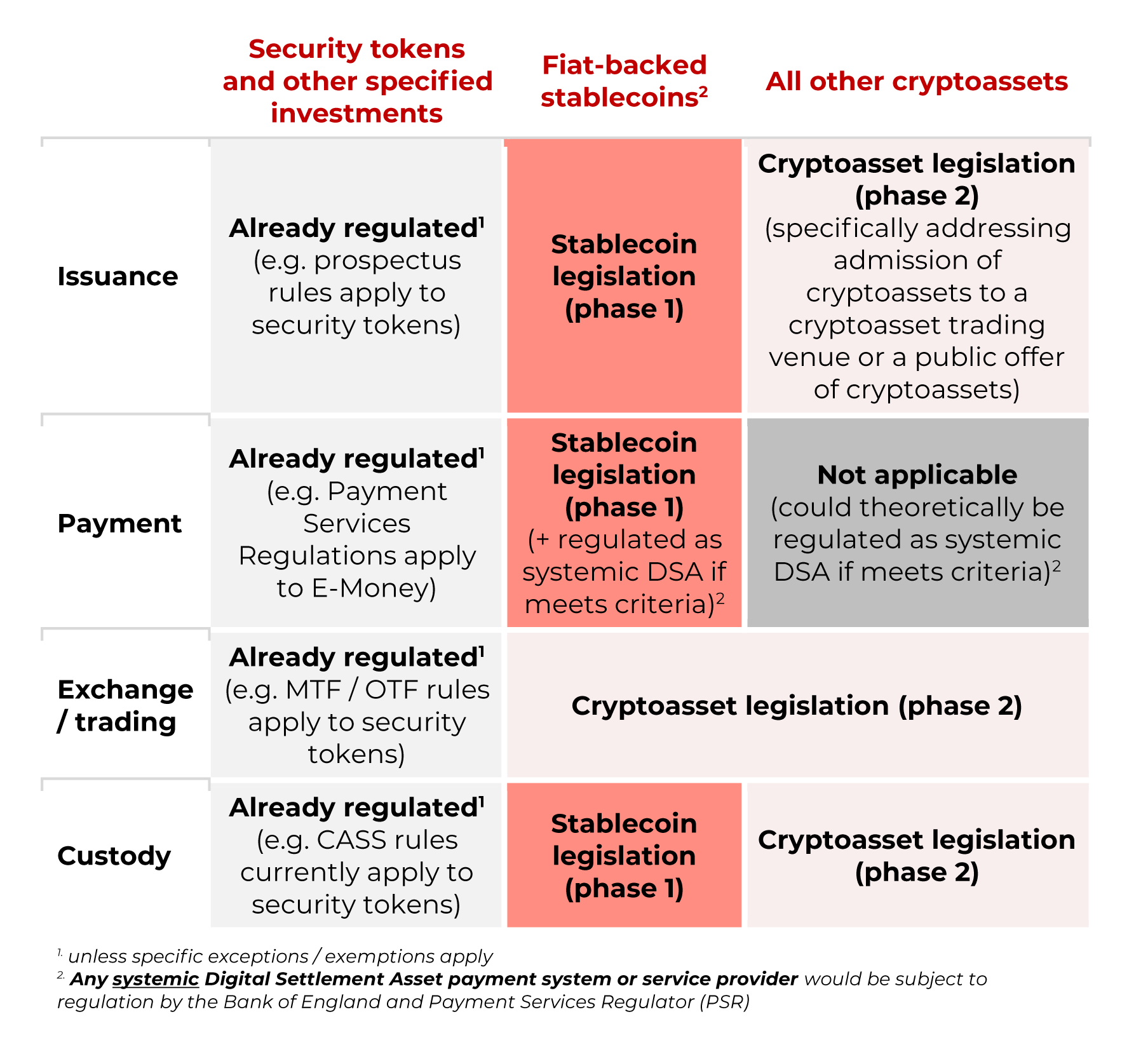

Crypto-assets will become subject to regulatory oversight through various phases, with phase 1 focusing on fiat-based stablecoins (including their custody) and phase 2 on other crypto-assets.

It is worthwhile to note that security tokens in digital form will continue to be regulated as “specified investments” under the RAO provided that their features mean that they are within the scope of this definition. Therefore, the existing custody rules applicable to “specified investments” will continue to apply, including the Financial Conduct Authority’s (“FCA”) Client Asset Sourcebook (“CASS”).8

Source: HMT Consultation

6.9 As a result of this approach, intermediaries providing custody services in respect of crypto-assets that constitute specified investments will need to comply with the existing requirements found in CASS. For crypto-assets that are not specified investments but nevertheless fall within the scope of the expanded regime.

As a result, HMT is proposing to apply and adapt Article 40 of the RAO for crypto-asset custody services, making suitable modifications to accommodate unique crypto-asset features, or putting in place new provisions where appropriate. In other words, a new regulated activity is proposed: “Safeguarding, or safeguarding and administering (or arranging the safeguarding or safeguarding and administering) of a crypto-asset other than a fiat-backed stablecoin and/or means of access to a crypto-asset (e.g., a wallet or cryptographic private key)”.

This is somewhat wider than the existing Article 40 activity as it would capture firms that only safeguard crypto-assets (e.g., firms that solely safeguard private keys). By contrast, to fall within the existing Article 40 activity, an intermediary must both safeguard and administer specified investments.

6.10 Intermediaries conducting this new activity will need to be authorised by the FCA and, as is the case under MiCAR, will be subject to various prudential, conduct and operational resilience requirements. CASS will be used as a basis for designing bespoke custody requirements for crypto-assets. Core components of the custody provisions are expected to be as follows:

(a) adequate arrangements to safeguard investors’ rights to their crypto-assets (e.g., restricting the commingling of investors’ assets and the intermediary’s own assets);

(b) adequate governance and organisational arrangements to minimise the risk of loss or diminution of investors’ custody assets; and

(c) accurate books and records of investors’ custody assets holdings.

6.11 HMT has indicated that it intends to take a proportionate approach which would not impose full, uncapped liability on the intermediary in the event of a malfunction or hack that was not within the intermediary’s control. Whether or not the Financial Services Compensation Scheme (“FSCS”) will be applied to losses suffered by investors is not yet clear. Despite calls for HMT to legislate to extend FSCS protections to the crypto-assets held in custody, HMT has indicated that it will leave this decision to the FCA once the FCA has considered following a consultation.

- ISDA, “Navigating Bankruptcy in Digital Asset Markets: Digital Asset Intermediaries and Customer Asset Protection” dated May 2023

- UNIDROIT, “UNIDROIT principles on digital assets and private law” dated May 2023

- UK Law Commission, “Digital Assets: Consultation Paper” dated 28 July 2022

- UK Jurisdictional Taskforce, “Legal Statement on Cryptoassets and Smart Contracts” dated November 2019

- Ruscoe v. Cryptopia Limited (in liquidation) [2020] NZHC 728 at [156](b).

- Quonine Pte Ltd v. B2C2 Ltd [2020] SGCA(I) 02 at [148].

- Regulation (EU) 2023/1114 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 May 2023 on markets in crypto-assets, and amending Regulations (EU) No 1093/2010 and (EU) No 1095/2010 and Directives 2013/36/EU and (EU) 2019/1937.

- The CASS provisions aim to protect investors’ rights to their assets while a firm is a going concern such that, if and when an intermediary becomes insolvent, assets are returned to investors promptly and as whole as possible.

In-depth 2023-280