Authors

Renewable energy is energy derived from natural sources that are naturally replenished at a higher rate than they are consumed, for example, sunlight and wind.

Governments have recently focused more attention on renewable energy – wind, solar, geothermal and hydroelectric – due to concerns over the security of supply, price volatility and environmental issues.

NEW: Energy transition in Asia 2024

Asia has been at the forefront of renewable capacity growth, consistently outperforming other regions over the past decade. Asia’s green energy capacity expanded 12% in 2022, which was the fastest rate among other major regions. According to Bloomberg, in 2022 APAC experienced an unprecedented surge in new investments, reaching a staggering $356 billion.

Some countries in Asia Pacific also committed to pumping the immense scale of investment stimulus into energy transition. Per a Det Norske Veritas® (DNV) report, South Korea’s 2050 Carbon Neutral Strategy and Green New Deal comprises of $135 billion in investments in green and digital technologies. Japan has pledged more than JPY150 trillion ($1 trillion) to decarbonization in line with its Sixth Strategic Energy Plan. Whereas Australia is seeking to provide approximately AU$24.9 billion (US$17 bilion) for energy transition purposes over the next 10 years.

In addition, Asia is also a sizeable region for renewable energy infrastructure deals. According to Enerdatics, “the deal volume for renewable energy assets in Asia more than tripled to $13.6 billion in 2021, as the number of transactions surged by 53% year-on-year to 75.” In 2022, this growth trend continued with renewable energy M&A deal value rising 11% to $19 billion in Asia Pacific.

Looking ahead, the primary energy demand in Asia is projected to grow at a 2.5% annual rate until 2035, which would make Asia’s share of the global primary energy demand close to 42% by 2035 and account for approximately 61% of the world’s primary energy demand increase by 2035.

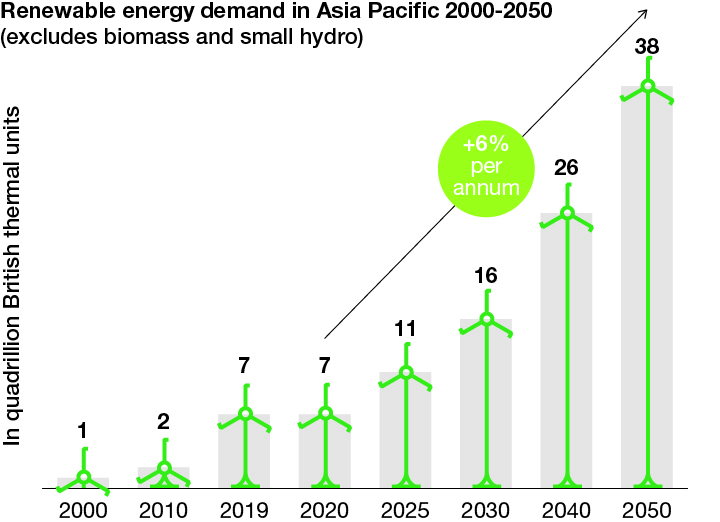

To meet such increasing energy demand and, at the same time, achieve the regional net-zero goals, Asia has to focus on the development of renewable energy projects as Asia’s demand for renewable energy is expected to grow at around 6% per annum until 2050.

Solar and wind are expected to be the main focuses for governments across Asia as they seek to bolster their energy security and push renewable energy agendas, as well as for companies expanding their portfolios in the region, according to a 2021 Boston Consulting Group (BCG) report. China, in particular, is predicted by DNV to lead solar energy by 2050, having secured a front-runner position in 2022 by generating 30% of global solar electricity. Additionally, China is anticipated to dominate most of the solar photovoltaic (PV) supply chain, where the majority of investments are expected to flow until 2030.

Per BCG projections, Asia could become the second-biggest offshore wind market, with capacity reaching 78 gigawatts (GW) by 2030 (a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 24% over the period 2021 to 2030). Per the DNV report, China currently stands out as a leading player in global onshore and fixed offshore capacities given the rapid rate of installations and economic incentives from the region's emerging carbon market in the power sector. DNV expects installed wind capacity, including off-grid, to be 0.8 terawatts (TW) by 2030, with onshore wind comprising 0.7 TW. The growth is projected to persist, with 2.5 TW of onshore, 430 GW of fixed offshore and 59 GW of floating offshore being anticipated by 2050.

This chart shows the predicted rise in renewable energy demand in Asia Pacific from 2000 until 2050, and it is anticipated that every year from now until 2050 will result in an approximate increase of 6% per annum in quadrillion British thermal units.

All of the aforementioned growth in renewable energy projects in Asia requires funding. Nevertheless, following the unprecedented levels of Covid-19-related expenditure by regional governments and their continuing efforts to dampen the effects of rising inflation, governments will struggle to fund the switch to renewable energy from public budgets. Reports suggest that the public sector in emerging Asia (and, in particular, in the developing members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)) cannot afford to pay for the energy transition itself. The annual infrastructure gap in Asia Pacific, which was estimated prior to the Covid-19 pandemic at $1.7 trillion, has likely expanded further post-pandemic, according to the Asian Development Bank.

Consequently, governments in emerging Asia will need to attract private capital into the energy transition infrastructure to meet their sustainability goals. As such, we expect to see a much greater role for private investment in Asia’s energy infrastructure sector than has historically been the case.

We continue to see strong demand for emerging Asia renewable energy infrastructure from both:

- Financial investors, such as sovereign wealth funds, large cap infrastructure funds, sustainable infrastructure funds, pension and insurance funds and family offices, all the way down to smaller scale blended and development finance providers, and

- Strategic investors, such as global oil majors, regional oil companies, infrastructure developers, utilities and the power businesses of family-owned conglomerates.

In relation to financial investors, more than $300 billion of private capital has accumulated worldwide in infrastructure funds, and all that dry powder is looking for a home. Asian renewable assets represent a potentially lucrative destination for funds as the region anticipates attracting nearly 40% of total global investment in renewable energy capacity by 2050. Given the post-pandemic recovery and consequent need for clean energy, Asia is an attractive proposition for infrastructure fund managers investing in renewable energy projects, as seen in Macquarie Asset Management’s third Asia-Pacific regional infrastructure fund, which closed at $4.2 billion; KKR’s $400 million investment into India’s Hero Future Energies; and BlackRock’s planned acquisition of Australia’s Akaysha Energy, a battery storage developer, for $690 million.

However, the current level of investment by infrastructure funds in Asia remains far behind what we see in Europe and the United States. While in Europe and the United States, infrastructure is an asset class that has been prevalent for well over a decade and there is now a well- defined and well-trodden path for funds deploying capital into new projects, in Asia, this asset category is still evolving and maturing.

Aside from funding, several other challenges need to be overcome in order to shift Asia away from carbon-intensive energy sources, particularly coal. These include Asia’s continued reliance on fossil fuels and investments in new coal plants. For example, coal used to account for 15% to 46% of China’s annual Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) energy investments, and China is the main supporter of new coal-fired power plants abroad. At the UN General Assembly in September 2021, China announced that it would not build new coal-fired power projects abroad. Instead, 55% of the BRI’s energy spend has already been redirected into renewables during the first half of 2023, according to the DNV report.

Moreover, according to a 22 September 2022 report by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, 16 such coal plants (having a combined capacity of 17 GW) that are in the pre-construction stage can be either transformed to renewable energy or reassessed for cancellation. Given that the permitting and/or financing agreements have already been concluded, a number of these projects would need to be completed to avoid being in breach of existing contractual obligations. Where no construction has begun, it is possible that these arrangements will be renegotiated to renewables.

There is a need for an accessible, stable and reliable grid. As more renewable sources of energy are added to the energy mix, grid accessibility and reliability increasingly becomes an issue globally and particularly in Asia, where many generation projects are in more remote areas and even those that are not can be constrained by inadequate grid reliability.

While some of the challenges are universal across all Asian markets, others are more prevalent in emerging Asia and, in particular, in the emerging markets of ASEAN. We have summarized below our selected observations on how investors are overcoming the challenges they face in investing in renewable projects in emerging ASEAN.

Challenges faced by investors in renewable projects in emerging ASEAN and how they are being mitigated

Dearth of investable renewable infrastructure assets and platforms

Given the infrastructure gap mentioned previously and the historical lag in completing operational assets in the region, few investable renewable infrastructure portfolios or platforms match the scale in ASEAN. This has been particularly challenging for investors looking to deploy large sums of capital in the region.

Another factor negatively affecting the supply of investible projects is the uneven availability of wind and solar resources in the region, which are required to ensure a smooth output, improving the reliability of supply and reducing the need for storage.

This scarcity of sizable operational renewable energy assets and platforms has resulted in significant competition for the few available assets. This has driven up valuations and created pricing expectation mismatches between buyers and sellers.

As a result, investors have diverted their attention and capital to other developing markets that are further down the energy transition journey and have relatively more developed renewable energy infrastructure and regulations, such as India.

Investors must navigate inconsistent regulatory, legal regimes

Diverse regulatory and legal regimes across ASEAN present challenges for investors who are looking to build pan-ASEAN portfolios and platforms.

Unlike in larger and more uniform markets, such as China and India, investors must possess the local regulatory, legal and cultural expertise necessary in each jurisdiction if they wish to successfully navigate the complexity of ASEAN’s regulatory and legal regimes to produce large portfolios.

Each electricity market within ASEAN is structured differently with varying levels of private involvement. What works for a developer or investor in Thailand will not necessarily work in Indonesia. This diversity and fragmentation reduce the economies of scale that can be achieved across a pan-ASEAN platform compared with what can be achieved in larger, more uniform markets in Asia.

Moreover, significant regulatory reform is required in a number of ASEAN countries in order to create a more efficient landscape for renewable energy investment. Investors face regulatory challenges, such as unattractive pricing structures, bankability issues, foreign ownership restrictions, sub-optional tendering processes, and the unpredictability of regulatory implementation. In some jurisdictions, laws created to encourage the growth of renewable energy are not fit for purpose and/or subject to constant tinkering or re-interpretation.

On the plus side, the current post-pandemic economic environment in which national budgets are under pressure, provides a good opportunity for the region’s governments to address regulatory issues faced by infrastructure investors in order to attract private capital for much-needed renewable energy projects.

Political, execution and economic risks: Each jurisdiction in emerging ASEAN presents a unique set of geopolitical, execution and economic risks.

Political risks: Such risks are present to varying degrees in all emerging ASEAN markets and are a critical consideration in the assessment of the viability of long-term renewables projects. Powerful vested interests in some countries have sought to hamper the progress of the energy transition.

Execution risks: Investment and project execution difficulties present significant challenges to the transactability of renewable opportunities in the region, especially for investors who are new to Asia.

Economic risks: The renewables industry in ASEAN is subject to the same post-pandemic economic risks faced by the wider economy, such as surging inflation, which impacts the costs of labor and equipment; rising interest rates; and supply chain disruption (equipment is currently manufactured in a limited number of countries, China in particular). The DNV report emphasizes global efforts to increase supply chain resilience by reducing the dependence on a single manufacturing hub. To achieve this, DNV forecasts that some production will be moving out of China to neighboring countries in Southeast Asia and the Indian Subcontinent.

- Financing: Limited debt financing availability and under-developed local debt markets in some jurisdictions hamper the attractiveness of renewable projects in the region and lessen the return on equity for investors. There is also a need for governments to provide credit support or enhancement in order to address some of the other challenges prevalent in these markets. Moreover, the rise of interest rates across the globe will likely have a negative impact on project viability.

As DNV highlights, while the European and the US central banks have increased interest rates to curb inflation, central banks in China and the Indian Subcontinent have been reducing interest rates. As such, industry stakeholders need to appreciate regional differences in central bank policies when assessing the borrowing costs. - Lack of reliable dispute resolution mechanisms: This challenge is not unique to the renewable energy sector, but it is a key consideration when structuring significant long-term capital investments.

Mitigations

Investors (both financial and strategic) have had to re-calibrate their strategies for ASEAN. Those who have entered the market by deploying strategies that were successful elsewhere in the world without making appropriate adjustments for the complexities of ASEAN have had to seriously rethink their approach.

Mitigation trends that we have observed include:

- Investors are increasingly willing to bear development and construction risk and are investing in greenfield and early-stage opportunities, where value creation opportunities (as well as the risks) are higher. Traditionally risk-averse and conservative investors, such as pension funds and family offices, are becoming more comfortable with development risk and investing directly in renewable assets rather than as limited partners in infrastructure or private equity funds.

- Investors are partnering with existing local developers in a bid to secure scarce talent and development pipelines and investing heavily in developer teams with proven regional track records to scale up new or existing platforms. Developer teams that have been involved in successful exits or have ASEAN- wide experience and solid development pipelines are particularly in demand.

- The efforts of specialist investors (such as impact and sustainable infrastructure investors) in backing early-stage projects in the region are starting to bear fruit. Such development finance is often funded by the governments of developed countries or by the philanthropic or impact investing arm of institutional investors and family offices. Although these projects are often fairly small in scale, the seed that such finance provided has resulted in the successful completion of a growing number of renewable projects which would not otherwise have been built. This progress is helping to alleviate the lack of investable operational assets.

- Due to the regulatory challenges involved in building highly regulated utility-scale renewable projects in the region, some investors have focused on opportunities where the regulatory hurdles are lower. We have observed this in the significant growth of the commercial and industrial rooftop solar market across ASEAN.

- Where independent developer teams are not available or where investors are seeking to scale, investors are partnering with local conglomerates by taking minority stakes in family conglomerate-owned renewable energy platforms or in the power and renewables divisions of family-owned conglomerates. In doing so, foreign investors are able to gain exposure to the relevant market and, at the same time, mitigate the myriad of commercial, regulatory and legal challenges by benefiting from the local conglomerate’s regulatory expertise and breadth, as well as the depth of local connections.

- Strategic investors, such as oil majors, regional energy companies and multi-national conglomerate groups, are seeking to leverage their existing local presence in other business lines to help grow their renewable energy and new energy businesses. Goodwill and relationships cultivated over time by other business divisions (with local governments, regulators, contractors and suppliers) are being utilized to help with the market entry into the renewables space.

- In jurisdictions where debt financing is difficult to obtain, investors and developers are willing to self-finance projects or seek alternative specialist finance from blended and other development finance providers.

- To mitigate against unreliable local dispute resolution mechanisms (including local judiciaries), where possible, investors and developers have opted to, subjecting their contracts to Singapore law and arbitration. Many regional renewable energy platforms have also chosen to site their head offices in Singapore and incorporate their ultimate and intermediate holding companies in the city-state to facilitate fundraising, joint ventures and exits with international counterparties.

What we can expect

Asia is tipped to lead renewable energy investments up to 2030. According to BloombergNEF, in the first six months of 2022, investments in solar and wind energy in Asia grew 33% and 16% respectively, compared to the same period in 2021. Investment activity is expected to be sustained by the region’s increasing population, economic growth and relatively small amount of installed capacity. Under the CIPP, Indonesia aims to reduce carbon emissions to 250 million metric tons for its on-grid system by 2030, achieving 44% renewable energy generation share. In Japan, growth areas include offshore wind and solar PVs. Whereas India will see expansion of wind and solar manufacturing capacity. Malaysia is targeting 20% clean energy generation by 2030 – the country is planning to add approximately 10 GW of renewable energy, representing a $12 billion investment opportunity, and it is also the third-largest PV cell producer in the world.

We also expect the following trends observed over the past years in Asia to continue impacting renewable energy projects in the region:

Regulation: Regulation will continue to evolve in the region. India is often cited as a key success story for the development and growth of a renewable energy industry. For instance, India launched the National Single-Window System. The portal provides investors and businesses with a one-stop-shop for the approvals required for the realization of renewable projects, while also facilitating investments in an interstate transmission system. Additionally, India’s regulations are fairly well defined and supported by capable regulatory bodies. Further growth of private investment in Indian energy transition infrastructure is expected due to its relative regulatory certainty, accommodating government policies and a judiciary that understands the industry.

Elsewhere, Vietnam has been developing its renewable energy market at breakneck speed driven by investor-friendly and accommodating policies in this space. For example, Vietnam implemented renewable policies such as feed-in tariffs that propelled the adoption of renewables, as well as advanced competitive tendering procedures to scale offshore wind. We expect that other emerging Asian countries will seek to follow the success of their neighbors and continue to improve the attractiveness of their regulatory regimes. As an example, in 2022, Indonesia issued a renewed regulatory framework for the development of renewable energy projects and relaxed its foreign investment negative list in response to stakeholder feedback on the shortcomings of the previous regulations.

Regional consolidation: As the regional market continues to grow, we expect to see consolidation in the renewable energy sector, such that larger and well-financed platforms will continue acquiring smaller players to improve critical mass and leverage cheaper financing and other benefits from economies of scale. Having observed this trend in the Indian market, we expect to see this occur in Southeast Asia as the regional renewable energy market grows and develops.

Investment patterns: The growth in the number of new entrants into the regional renewable energy market (and the ASEAN market in particular) will continue. We expect to see financial and strategic investors enter the region by way of platform acquisitions and joint ventures with existing developers or by doing it alone. In particular, global institutional investors and utilities will continue to seek to grow their presence in emerging Asia, as demonstrated by the recent spate of deal-making by Canadian, European and Japanese infrastructure funds, as well as pension funds and utilities in Southeast Asia.

Private capital will continue to flow from infrastructure funds to renewable energy projects in Asia despite the current market disruptions due to the perceived lower risks, steady cash flows and inflation protection offered by infrastructure as an asset class. A number of recent and well-publicized exits by global infrastructure investors from their investments in regional renewable energy platforms, as well as the increase in the number of well-capitalized trade buyers (such as regional power groups), will increase the attractiveness of such investments. Infrastructure investors will become increasingly comfortable with greenfield investments in the region as a matter of necessity. As such, we expect to see such investors take greenfield risks by acquiring existing operational platforms and/or development pipelines and growing them.