In September 2018, India’s Ministry of Corporate Affairs appointed the Competition Law Review Committee (CLRC) to evaluate whether the country’s Competition Act of 2002 (the Act) was keeping pace with its burgeoning economy. The mandate of the CLRC was to review international best practices and competition law regimes to determine whether the Act needed reform to ensure “the development of competition and fair play . . . in the Indian market.”1 The efforts of the CLRC culminated in the proposed Competition (Amendment) Bill, 2020 (the Amendment).

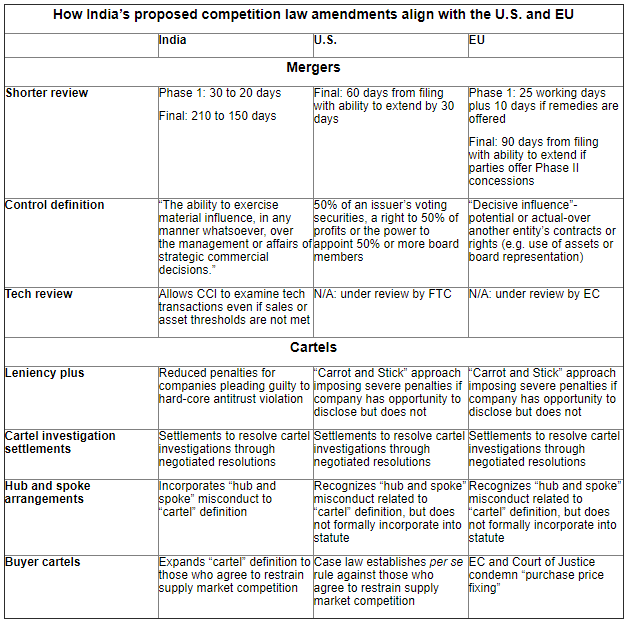

The Amendment recommends several key changes in merger review and cartel enforcement that would bring the Act more in line with U.S. and EU regulations. The Amendment represents a significant step towards cross-border harmonization for companies doing business in these jurisdictions, as well as the development of uniform international standards, given India’s status as the fifth-largest global economy.

Changes to merger control and tech combinations

Shorter review period. The Act’s current 30-day deadline for Phase I review, during which the Competition Commission of India (CCI) forms its initial opinion as to whether there is an “appreciable adverse effect on competition” in the relevant market, is already consistent with U.S. and EU timelines,2 but the Amendment would further shorten it to 20 days. The Amendment also would reduce the time for the CCI to render its final decision from 210 days to 150 days. At first glance, this reduction still exceeds the U.S. and EU regulations, which provide that the reviewing agency must render a decision within 60 and 90 days of the parties’ filing, respectively. The reality is that the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the U.S. Department of Justice, Antitrust Division (the Division) can further extend the second 30-day waiting period if there is a lingering concern that the combination would “substantially lessen competition.”3 Similarly, the Directorate-General for Competition of the European Commission (EC) may have more time to review a transaction that may “significantly impede competition”4 if the parties offer concessions after the fifty-fifth day of a Phase II investigation or otherwise agree to an extension.

“Control” defined. Although the Act states that merger reporting requirements are triggered by acquiring control at or above certain assets thresholds or enterprise values, it does not define control other than to say that it “includes controlling the affairs and management” of one or more enterprises.5 The Amendment defines “control” as “the ability to exercise material influence, in any manner whatsoever, over the management or affairs or strategic commercial decisions.” This revision more closely aligns with the U.S. regulation defining control as 50 percent of an issuer’s voting securities, a right to 50 percent of profits or the power to appoint 50 percent or more board members,6 and the EU’s focus on “decisive influence” over another entity’s contracts or rights, such as use of assets or board representation, regardless of whether the influence is or will be actually exercised.7

Tech review. One area where India may be at the forefront of antitrust enforcement is its review of tech combinations. The Amendment would empower the CCI to examine these transactions even if the asset or sales thresholds are not met-a measure that would allow the agency to scrutinize tech transactions that would otherwise escape review. The FTC is currently examining past tech transactions that were not reportable under the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act (HSR) to determine whether there is a gap allowing dominant companies in the sector to acquire upstart rivals, but the agency has yet to offer a recommendation (though the FTC and the Division always have the right to review non-HSR reportable transactions). The EC is undertaking a comparable study borne of the same concern, and its conclusion is pending.