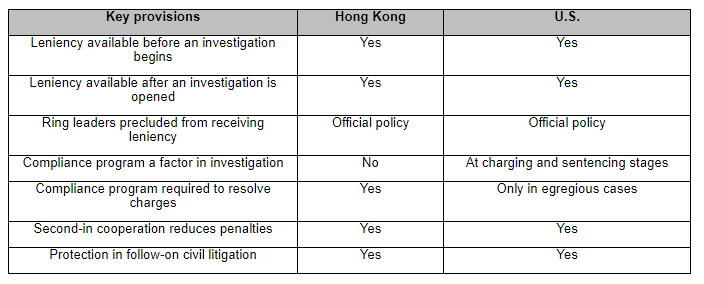

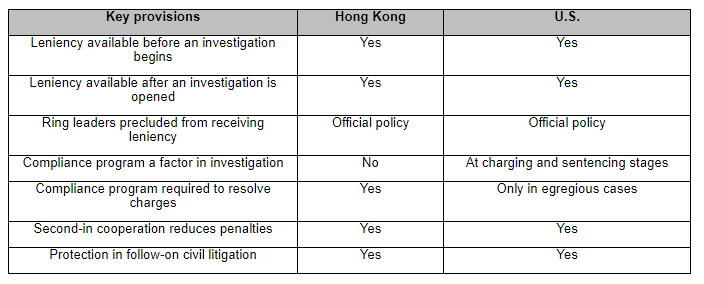

Type A and Type B leniency. Two pillars of the U.S. leniency program are Type A and Type B leniency. The Division grants the former when a leniency applicant is the first to self-report its role in cartel misconduct before the Division has opened an investigation. In contrast, Type B leniency is available before or after the inception of an investigation, when the Division does not yet have sufficient evidence against the applicant to result in a sustainable conviction. The Hong Kong leniency program now parallels the U.S., with the same benchmarks characterized as “Type 1” and “Type 2” leniency options.

Protections for current and former employees. Type A leniency in the U.S. provides immunity to current directors, officers and employees who sufficiently cooperate with the investigation. With Type B leniency agreements, however, the Division in its discretion may exclude “current directors, officers, and employees who are determined to be highly culpable.”4 The Commission, however, does not make such a distinction in its leniency policy. Moreover, the Hong Kong program provides an additional incentive to cooperate because, pursuant to the leniency agreement, the Commission will not seek a disqualification order that would prevent an individual from serving as a director, which is defined as “any person occupying the position of director or involved in the management of a company.”5 As a result, the Hong Kong leniency program now offers more clarity and incentives for employees than its U.S. equivalent.

With both Type A and Type B leniency, the Division has always had discretion to exclude former employees from a leniency agreement but, in 2017, appeared to harden its stance, when it announced that former directors, officers and employees “are presumptively excluded from any grant of corporate leniency.”6 Although the Commission also retains discretion as to its treatment of former agents, officers, employees and partners, there is no presumption to exclude them from the leniency agreement in the Hong Kong program—a more tenable proposition for a former employee deciding whether to cooperate.

Leniency policy for individuals. Hong Kong’s revised leniency program includes, for the first time, a leniency policy for individuals.7 This policy parallels that of the U.S., including that leniency is not available to the “ringleader” of a cartel and will only be granted to the first individual to report the cartel where a leniency marker has not already been granted to a company. Now that Hong Kong has individual leniency, companies will not only compete with co-conspirators, they may be competing with their own employees for first-in position to qualify for leniency.

Treatment of the cartel ring leader. Another way in which the Hong Kong leniency program mirrors the U.S. counterpart is its insistence that the cartel ring leader – i.e., the leader or the originator of the activity or one that coerced other conspirators to engage in cartel activity – cannot qualify for leniency.8 However, some members of the U.S. antitrust defense bar maintain that, in practice, the Division has largely ignored this criterion when necessary to further investigations – particularly, if “leniency plus” is in play. Indeed, in its 2017 FAQs, the Division explained that “[e]xclusion under the condition is rare and wherever possible, the Division has construed or interpreted its program in favor of accepting an applicant into the Leniency Program in order to provide the maximum amount of incentives and opportunities for companies to come forward and report their illegal activity.”9 Similarly, the Hong Kong leniency policy notes that “[w]herever possible, the Commission will construe or interpret the ringleader ground of this Policy in favour of accepting a leniency applicant in order to maximise incentives and opportunities for companies to come forward and report their cartel conduct.”10 As the Hong Kong leniency program gains traction, it will be interesting to see if the provision is more strictly adhered to in Hong Kong than in the U.S. or if the Commission will likewise construe the definition of “ringleader” very narrowly.

Mandatory compliance program. The Hong Kong Competition Commission was the first leniency regime to require a compliance program as a condition of leniency. The Commission specifically mandates that applicants be “prepared to continue with, or adopt and implement”11 a compliance program that meets the standards of the agency. This added requirement reflects a measure that Mr. Snyder consistently championed while at the Division.12

By contrast, in the U.S., compliance programs are not a mandatory condition of receiving leniency. In egregious cases, the Division may ask the relevant U.S. district court to appoint an external monitor to ensure that the leniency applicant “develops an appropriate culture of corporate compliance.”13 Monitors have been appointed in several cases, including Panasonic Avionics Corporation and Hoegh Autoliners, AS. In July 2019, the Division announced that it will weigh whether a company has an effective compliance program at the charging and sentencing stages of the criminal process.14 The Division’s new approach “allows prosecutors to proceed by way of a deferred prosecution agreement (DPA) when the relevant Factors, including the adequacy and effectiveness of the corporation’s compliance program, weigh in favor of doing so.”15 Compliance programs are also considered in determining corporate fines and probation recommendations under the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines.16 The Division issued guidelines in 2019 for corporate compliance programs, which detailed nine factors prosecutors will consider in evaluating a corporate compliance program.17

The Commission’s mandatory compliance program provision and the Division’s evolving position on compliance programs illustrate the increasing importance of compliance programs, not only in prevention or early detection of antitrust violations, but also as a consideration in determining the penalty for antitrust violations. Companies and their counsel would be wise to review and study the Division’s guidelines for corporate compliance programs, which offer a useful roadmap for companies in designing, evaluating or updating their own programs.

Second-in cooperation. The Commission strongly encourages companies that cannot obtain leniency to vie for the “second-in” position. Companies that do not qualify for leniency can opt to cooperate with the Commission’s investigation under the Cooperation and Settlement Policy for Undertakings Engaged in Cartel Conduct. Cooperating companies may receive a cooperation discount in fees, which may range from 50% to less than 20% based on the timing, nature, value and extent of cooperation provided by the undertaking. The Commission may also agree not to bring any proceedings against any current and former officers, employees, partners and agents of the undertaking as long as these individuals provide complete, truthful and continuous cooperation.18

Similarly, the Division has long touted second-in cooperation as a way for a company to reduce the volume of “affected commerce,” which is the underpinning of corporate fines and individual prison terms.19 As noted above, the Division upped the ante when it announced that it may offer deferred prosecution agreements to companies that are not able to secure first-in position and leniency, weighing factors at the charging stage such as whether the company’s compliance program, and whether it “promptly” self-reports, cooperates in the investigation and takes remedial action. 20

Civil litigation protection. In the U.S., where follow-on civil litigation is an inevitable consequence of entering a plea agreement, the Division has been a powerful advocate of the Antitrust Criminal Penalty Enhancement and Reform Act of 2004 (ACPERA).21 Pursuant to ACPERA, a leniency applicant that provides timely and satisfactory cooperation to plaintiffs may qualify for single damages rather than the treble damages and joint and several liability imposed by the Clayton Act. Hong Kong offers even stronger protection for leniency applicants against follow on civil litigation. Section 110(3) of the Hong Kong Competition Ordinance immunizes a Type 1 leniency applicant from having to admit to an infringement, which is necessary pre-condition for a follow-on claim in that jurisdiction. Note, however, that the Commission may issue an infringement notice to a Type 2 leniency applicant, as set forth in the Hong Kong leniency policy.

***

The Commission has embraced the principles of U.S. leniency and incorporated them into its own program with a few notable differences, and in some respects offering even stronger incentives for leniency applicants or those considering cooperation. If a company is considering a multi-jurisdictional leniency filing that includes Hong Kong, the precedents established in U.S. investigations may provide it with insight into how the Commission will deal with cartel misconduct. At the same, the Commission has demonstrated a willingness to forge its own path with cutting-edge policies that encourage cooperation and a culture of compliance. Hong Kong is now a jurisdiction to watch and a model for agencies that want to revitalize their own leniency programs.

To learn more about current and potential trends in international cartel enforcement, please contact a member of our antitrust and competition team in the U.S., or Peter Glover and Asha Sharma in Asia.

Comparison of the Hong Kong and U.S. leniency programs

- Hong Kong Competition Commission, “Competition Commission revises leniency programme for cartel conduct” (April 16, 2020) available at compcomm.hk/press.

- “Leniency plus” is when a company that is not a candidate for leniency in one product market is eligible for leniency in one or more other markets because it can provide “substantial assistance” to the Division. See U.S. Dep’t of Justice, “Frequently Asked Questions about the Leniency Program and Model Leniency Letters,” originally published November 19, 2008, update published January 26, 2017, (hereinafter, U.S. Leniency FAQ) at 9, available at justice.gov/leniency-program.

- See Hong Kong Competition Commission, “Cooperation and Settlement Policy for Undertakings Engaged in Cartel Conduct” (April 16, 2020) available at compcomm.hk/legislation_guidance.

- See U.S. Leniency FAQ, supra note 1, at 11.

- Competition Ordinance § 101 (2013).

- Id. at 22.

- Hong Kong Competition Commission, “Leniency Policy for Undertakings Engaged in Cartel Conduct” (April 16, 2020) available at compcomm.hk/leniency_policies.

- U.S. Leniency FAQ at 16 (emphasizing that the leniency policy refers only to “‘the leader’ and ‘the originator of the activity,’ rather than ‘a’ leader or ‘an’ originator.’” Accordingly “[a]pplicants are disqualified from obtaining leniency on this ground only if they were clearly the single organizer or single ringleader of a conspiracy.”); Leniency Policy for Undertakings at 3 n.2.

- U.S. Leniency FAQ at 16.

- Leniency Policy for Undertakings at 3 n.2.

- Id. at 8.

- See, e.g., Brent C. Snyder, Deputy Ass’t Att. Gen., “Compliance is a Culture, Not Just a Policy” (September 9, 2014) available at justice.gov/compliance-culture-not-just-policy.

- See Makan Delrahim, Ass’t Att. Gen., “Evaluation of Corporate Compliance Programs in Criminal Antitrust Investigations” (July 2019) available at justice.gov/1182001.

- See, e.g., Scott D. Hammond, “Measuring the Value of Second-In Cooperation in Corporate Plea Negotiations” (March 29, 2006) available at justice.gov/measuring-value-second-cooperation.

- See Makan Delrahim, Ass’t Att. Gen., “Wind of Change: A New Model for Incentivizing Antitrust Compliance Programs” (July 11, 2019) available at justice.gov/speech.

- Supra note 10.

- Supra note 10. The nine factors are: “(1) the design and comprehensiveness of the program; (2) the culture of compliance within the company; (3) responsibility for, and resources dedicated to, antitrust compliance; (4) antitrust risk assessment techniques; (5) compliance training and communication to employees; (6) monitoring and auditing techniques, including continued review, evaluation, and revision of the antitrust compliance program; (7) reporting mechanisms; (8) compliance incentives and discipline; and (9) remediation methods.”

- See Hong Kong Competition Commission, “Cooperation and Settlement Policy for Undertakings Engaged in Cartel Conduct” at 7-8 (April 2019) available at compcomm.hk/cooperation_settlement_policy.

- See, e.g., Scott D. Hammond, “Measuring the Value of Second-In Cooperation in Corporate Plea Negotiations” (March 29, 2006) available at justice.gov//measuring-value-second-cooperation.

- See Makan Delrahim, Ass’t Att. Gen., “Wind of Change: A New Model for Incentivizing Antitrust Compliance Programs” (July 11, 2019) available at justice.gov/speech.

- Section 213(b) and (c), 15 U.S.C. 1 notes.

Client Alert 2020-253