The current regulatory environment may be misleading in that respect. Indeed, the measures adopted in recent weeks,1 which are designed to ensure that companies and their constituent parts continue to operate, facilitate procedures for meetings of shareholders and corporate bodies and allow for them to be more flexible. These measures are intended to compensate for the obstacles to physical meetings. One might expect that such flexibility, together with the absence of immediate judicial review, the activities of courts being greatly reduced, would give companies the opportunity to dismiss executive directors. However, the current situation does not relieve companies of the obligation to carry out dismissals in a manner that is not vexatious, abusive or unfair. Furthermore, certain measures usually validly taken by companies in the context of the dismissal of a director may, in the wider current context, be more difficult to carry out and even be considered vexatious.

First, it should be recalled that the body that has the competency to dismiss a director is generally the one in a position to appoint them. These bodies are precisely those whose meeting procedures have been eased to cope with the current lockdown measures: in large part, the arrangements adopted by the new legal measures set out the procedures for allowing meetings of the administrative, supervisory and management bodies of companies both remotely and by written consent. Shareholders’ meetings and deliberations can take place behind closed doors or by phone-conference, videoconference or written consultation. These new provisions remain, for the time being, applicable until 31 July 2020.

There is a risk that the new legal framework and the current exceptional circumstances could result in companies wishing to dismiss a director being remiss in their duties. However, companies should bear in mind that these new mechanisms must comply with other principles provided by French company law, which remain in force. While the freedom to dismiss directors applies as a general principle, there are safeguards protecting them from what might be viewed as an abusive use of the right to dismiss.

The principle of free dismissal of company directors

Directors (administrateurs), supervisory board members, managing directors (directeurs généraux), deputy managing directors (directeurs généraux délégués), executive board members of a public limited company (société anonyme – SA), and managers of a limited liability company (société à responsabilité limitée – SARL), general partnership (société en nom collectif – SNC) or limited partnership (société en commandite simple – SCS), may be freely dismissed, which means that such dismissal may occur at any time, without notice or compensation. This principle of free dismissal is a matter of public policy and any conflicting clause in the articles of association or any agreement is null and void to the extent that it suppresses, limits or impedes such freedom. By way of exception, this principle does not apply to the managers of a partnership limited by shares (société en commandite par actions – SCA) and directors of a simplified joint stock company (société par actions simplifiée – SAS), for whom the terms of dismissal are freely determined by the articles of association.

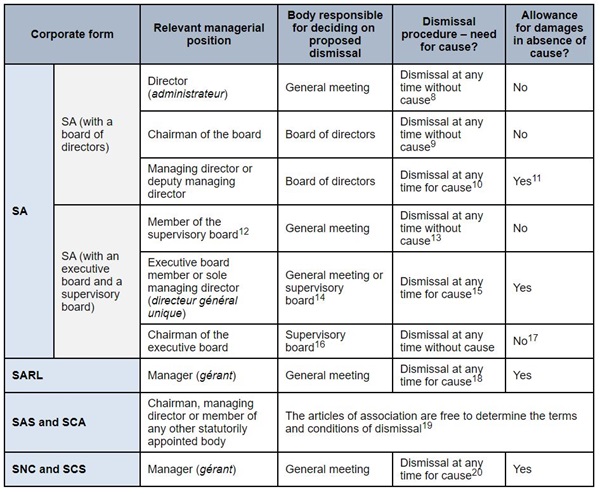

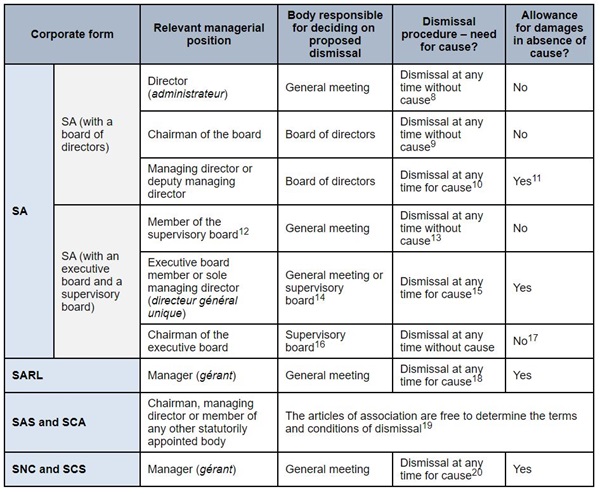

Nevertheless, even if freedom remains the rule, dismissal sometimes requires a cause (juste motif), failing which the dismissal may trigger the payment of damages to the director (see the summary table in the Appendix).

In practice, the cause may be misconduct (a breach of the law or the articles of association, mismanagement, refusal to convene a general meeting, etc.) or, in the absence of misconduct, any conduct or behaviour likely to compromise the company’s interests or its operations.

In the current circumstances, valid grounds for dismissal could include certain failings on the part of the director if these can be clearly identified. It should also be anticipated that these same circumstances may make it particularly difficult to assess the capabilities expected of directors, which are not necessarily the same as those on the basis of which they were previously appraised or recruited and, likewise, the impact of the crisis on performance may similarly make any failures attributable to directors less clear-cut.

It should be added that the grounds for enforcing any emergency measures in support of the dismissal process, in particular with regard to matters of evidence (finding of article 145 of the French civil procedure code), will doubtless be more difficult to justify if the crisis has had a significant impact on the company’s performance, and also, in practical terms, in light of the suspension of the activities of the courts and many judicial officers, which will certainly not facilitate the implementation of such measures in the usual swift and sudden manner.

A freedom limited by the concept of wrongful use of the right of dismissal

Even when a cause is not required for dismissal, company directors enjoy the protection afforded to them by case law against abuse of the right of dismissal.

Dismissal is deemed conducted in an abusive way if made in a manner that causes insult or is vexatious to the director (i.e., damage to their reputation and honour) or if it is carried out without the director having had the opportunity to present their case to a meeting of the body called on to vote on the proposed dismissal or without the director having been made aware of the grounds for dismissal.

- Dismissal must not be in circumstances liable to cause insult or be vexatious

Insulting or vexatious conduct includes the following:

- asking the director to hand over the company’s keys immediately or to leave the premises without delay;2

- legal publication in the Trade and Companies Register of the dismissal of the director on grounds of serious misconduct;3

- where the director was dismissed only from the position of CEO of one of the group companies, removal of the tools necessary for them to exercise any other duties as a corporate officer for which they remain responsible at the date of dismissal;4 and

- the intervention of a court bailiff and the police in the presence of a third party.5

On the other hand, denying the dismissed director with access to the computer server, terminating their email address and telephone number, or requesting that they return their company vehicle immediately and vacate their accommodation within one month, does not, in principle, constitute insulting or vexatious behaviour.6

However, in the current situation, companies should carefully consider whether sudden measures, such as terminating email addresses and telephone numbers, are likely to be considered vexatious. In times of crisis, courts are more responsive to the circumstances of the financially weaker party and their capacity to ‘bounce back’.

- Dismissal is subject to a duty of loyalty

This duty of loyalty implies that both the adversarial principle and the right of defence must be respected.

In practice, French law requires that a director be made aware of the grounds for their dismissal before any decision is taken (even if the law applies to a director who can be dismissed at any time without cause) and that they be given the opportunity to present their case before the vote is taken.7 Holding meetings remotely will certainly not facilitate respect for and compliance with these two principles and therefore must be managed with particular care.

Finally, judges called upon to assess a wrongful dismissal will not only look at the grounds for the dismissal: they will also take into consideration the circumstances surrounding such dismissal. Consequently, a dismissal may be wrongful even if it is on the basis of the gross misconduct of the director. Once the time comes for the trial, any dismissal carried out with haste in the current situation could be judged sternly if wrongfully conducted. It should be noted, however, that the damages which may be awarded to the wrongfully dismissed director must compensate a loss separate from that resulting from the dismissal itself.

Appendix

Our Reed Smith Coronavirus team includes multidisciplinary lawyers from Asia, EME and the United States who stand ready to advise you on the issues above or others you may face related to COVID-19.

For more information on the legal and business implications of COVID-19, visit the Reed Smith Coronavirus (COVID-19) Resource Center or contact us at COVID-19@reedsmith.com.

- Empowered by emergency law No. 2020-290 of 23 March 2020 to address the COVID-19 pandemic, the French government has adopted a series of measures relating to the procedures for general meetings and deliberations of corporate bodies under private law. These measures are set out in two enactments: Order No. 2020-321 of 25 March 2020 and Decree No. 2020-418 of 10 April 2020.

- Court of Cassation, Commercial Chamber, 9 November 2010, No. 09-71284

- Paris Court of Appeal, 30 April 2014, No.13/12230

- Court of Cassation, Commercial Chamber, 15 May 2012, No. 11-15497

- Paris Court of Appeal, 29 June 2010, No. 08/07998

- Court of Cassation, Commercial Chamber, 25 May 2017, No. 15-21633

- Court of Cassation, Commercial Chamber, 14 May 2013, No. 11-22845

- Article L. 225-18 of the French commercial code.

- Article L. 225-47 of the French commercial code.

- Article L. 225-55 of the French commercial code.

- If the managing director is also the chairman of the board, the rules applicable to the chairman shall prevail.

- The members of the supervisory board are not executive managers in the strictest sense as they are only entrusted with a supervisory role. The chairman of the supervisory board does not qualify as a person exercising executive, managerial or administrative duties.

- Article L. 225-75 of the French commercial code.

- If the articles of association so provide – L. 225-61 of the French commercial code.

- Article L. 225-61 of the French commercial code.

- The French commercial code is silent on the grounds for the dismissal of the chairman of the executive board if the chairman remains a member of the board – the supervisory board has the power to appoint the chairman of the executive board and therefore has the power to dismiss them.

- French law provides for damages for absence of cause only in the case of members of the executive board, and this provision is not called into question where the dismissal only relates to the duties of the chairman of the executive board.

- Article L. 223-25 of the French commercial code.

- SAS: article L. 227-1 of the French commercial code precludes the application of article L. 225-47 of the French commercial code – SCA: article L. 226-1 of the French commercial code precludes the application of article L. 225-47 of the French commercial code.

- SNC: article L. 221-12 of the French commercial code; SCS: article L. 221-12 of the French commercial code with reference to article L. 222-2 of the French commercial code.

Client Alert 2020-304