Key takeaways

- The Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR) is the newest addition to the European Commission’s (EC) regulatory arsenal, targeting subsidies granted by non-EU states.

- The FSR can be triggered by participating in concentrations involving a target active in the EU or in public procurement bids.

- The EC also reserves the right to carry out investigations against foreign subsidies in any situation.

- Businesses are required to track all of their transactions with non-EU countries as regards their receipt of foreign financial contributions (FFCs).

- Businesses will be subject to stringent notification and reporting obligations if they trigger the application of the FSR.

- The tracking of FFCs received by companies can be burdensome and difficult in practice.

Introduction

The Foreign Subsidies Regulation1 (FSR) entered fully in force on 12 October 2023 bringing with it onerous obligations for multinational companies. Its expansive definition of financial contributions means businesses with global operations must closely monitor their dealings with non-EU states and entities controlled by them. While the FSR was originally proposed more than three years ago, in June 2020, many businesses remain unprepared for the practical implications of the FSR on their activities, especially in light of the new concepts it introduces into the regulatory landscape, for which limited guidance currently exists. More clarifications are expected as the European Commission (EC) develops its case practice and grapples with the first notifications under the FSR. Until then, businesses are advised to take a pragmatic but diligent approach to complying with the FSR.

Background

The FSR fills a regulatory gap in the EU’s regulatory arsenal protecting competition. It aims to tackle foreign non-EU subsidies that distort the level playing field in the EU single market by applying similar concepts to those under its State aid framework for examining subsidies granted by EU member states. Therefore, the FSR will address the growing concerns that EU-based companies are significantly disadvantaged when competing against companies that are heavily subsidised by foreign non-EU states. Such foreign subsidies could enable their beneficiaries to outbid rivals in public tenders, to outprice businesses that did not benefit through similar subsidies, and could even facilitate the acquisition of EU companies by allowing these beneficiaries of foreign subsidies to offer excessively high purchase prices.

Prior to the FSR, the EU could not intervene to prevent these foreign subsidies. EU State aid law only applies to subsidies granted by EU member states, while merger control and antitrust rules serve different purposes. Some subsidies could be investigated by the EU through its trade defence instruments (anti-subsidy and anti-dumping rules), but these instruments only apply to the importing of goods into the EU. They do not cover the import of services, nor can they be used to tackle foreign subsidies regarding the production of products within the EU. Therefore, the FSR will complement the use of trade defence instruments, with the recent anti-subsidy investigation on Chinese electric vehicles being a candidate for a parallel ex officio investigation under the FSR.

It is important to note that despite the rhetoric about the FSR being centred around the protection of EU companies from subsidised foreign companies, the FSR affects EU and non-EU companies alike. EU companies which receive or deal with third countries could be subject to notification obligations or an ex officio investigation in the same way as non-EU companies, ensuring that the FSR is compatible with WTO rules.

FSR triggering events and notification thresholds

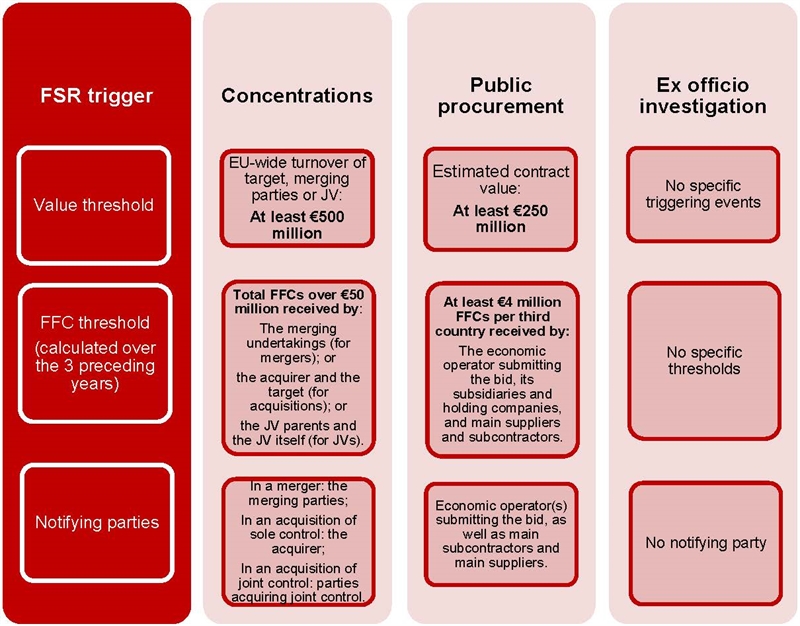

The FSR includes three different triggers to tackle foreign subsidies: the carrying out of an M&A deal to acquire a target with substantial EU revenues, participating in a public procurement bid in the EU, and being the target of a discretionary investigation by the EC.

Notification-based procedure to investigate concentrations

Under the FSR, concentrations meeting certain thresholds regarding turnover and foreign financial contributions (FFCs)2 received by the relevant parties need to be notified to the EC. A concentration is defined in the same way as under the EU’s Merger Control Regulation,3 covering a change of control on a lasting basis resulting from any of the following:

a. The merger of two or more previously independent undertakings or parts of undertakings

b. The acquisition, either individually or jointly, whether by purchase of shares or assets, by contract or by other means, of direct control of the whole or parts of another undertaking

c. The creation of a joint venture performing on a lasting basis all the functions of an autonomous business

The obligation to notify a concentration under the FSR arises when:

a. At least one of the merging undertakings, the target of an acquisition, or the joint venture is established in the EU and generates at least €500 million turnover in the EU; and

b. The relevant undertakings, as the case may be, received combined aggregate FFCs exceeding €50 million in the three years preceding the concentration, where the relevant undertakings are:

i. In the case of a merger, the merging undertakings

ii. In the case of an acquisition, the acquirer and the target

iii. In the case of a joint venture, the undertakings creating the joint venture and the joint venture itself.

Concentrations that are subject to a notification obligation are subject to a standstill obligation, requiring that the parties do not complete their transaction until the EC grants clearance or the relevant deadline has passed.

Notification-based procedure to investigate bids in public procurement

In the case of public procurement bids, the notification obligation arises where:

a. An economic operator submits a bid during a public procurement procedure whose estimated value exceeds €250 million; and

b. The economic operator (and its related parties) received aggregate FFCs in the three years prior to the notification equal to or greater than €4 million per third country.

Additionally, a notification will be required where the thresholds above are met, but the public procurement procedure is divided into lots, and the value of the lot or the aggregate value of all the lots for which the economic operator submits a bid is equal to or greater than €125 million.

A standstill obligation arises in notifiable public procurement bids as well, requiring that the economic operator who submitted the notification cannot be awarded the contract prior to receiving the EC’s clearance.

However, the public procurement tool under the FSR differs from the concentration tool, in that even if the economic operator did not reach the FFC threshold, it will be required to sign a declaration that it received no notifiable FFCs, and it is still obligated to disclose, in a list, all FFCs it received in the last three years preceding the declaration.

Ex officio procedure to investigate all other market situations

The ex officio powers of the EC allow it to review distortions arising due to foreign subsidies granted to companies active in the EU and include the power to examine concentrations and public procurement bids that do not meet the thresholds of the notification-based tools. The EC can use its investigative powers to request detailed information regarding the foreign subsidies and conduct inspections both within and outside the EU.4

Interested third parties, such as a competitor, could attempt to use the EC’s new FSR investigation toolbox as a sword to oppose deals or public procurement bids that are not in their interest. Accordingly, the EC has already received several complaints against companies who have reportedly received foreign subsidies, with a lot of publicity specifically centred around the potential use of the FSR against state-owned football clubs.5

However, the EC is unlikely to currently have the required workforce to make extensive use of its ex officio powers, with most of the FSR case handlers likely focusing on reviewing the mandatory notifications due to the strict deadlines included within the FSR notification regime. The decision to open an ex officio investigation is inherently a political one, and it will be interesting to see where the EC chooses to make use of these powers.

Figure 1 below summarises how all three triggers work in practice.

Figure 1: FSR triggering events and respective cumulative thresholds

EC’s enforcement powers

In all three of the above cases, the EC will assess the potential negative impact of the specific subsidies under investigation on the EU’s internal market, weighing them against any possible positive impact they may have within the EU, or in the context of a public policy interest recognized by the EU, such as environmental benefits or the creation of jobs within the EU. If the negative distortions outweigh the positive impact, the EC may impose redressive measures to remedy the situation, ranging from structural remedies (divestment of assets, unwinding of a concentration) to behavioural remedies (third-party access obligations, licensing on FRAND terms,6 repayment of a foreign subsidy, etc.). Investigated businesses can offer commitments to address the EC’s concerns regarding the distortive foreign subsidies, which, if accepted by the EC, become legally binding. Non-compliance with such commitments can lead to fines or periodic penalty payments.

What are Foreign Financial Contributions?

The most criticized part of the FSR is the wide scope of the definition given to financial contributions. This expansive definition captures all forms of contributions, regardless of their nature and rationale, and includes, inter alia:

a. Any transfer of funds or liabilities, such as grants, capital injections, loans, loan guarantees, below-cost financing, fiscal incentives, debt forgiveness, setting off of operating losses, compensation for financial burdens imposed by public authorities, and debt-to-equity swaps);

b. Any foregoing of revenues that are otherwise due, such as tax exemptions and the granting of special or exclusive rights without adequate remuneration); and

c. the provision or purchase of goods or services, even if at fair-market terms and prices.

The above categories are not exhaustive, and all forms of financial contributions are relevant at the notification stage, regardless of their type or value.

Such financial contributions are considered foreign if they are provided by:

a. A third country’s central government and its public authorities at all other levels; or

b. A foreign public entity or a private entity whose actions can be attributed to the third country.

The question of whether an entity’s actions can be attributed to a third country requires a fact-specific assessment which will be heavily influenced by the EU’s caselaw on State aid law and the concept of imputability of an act to a state. The recommended approach for businesses for the purposes of monitoring the FFCs they have received is to include any financial contributions they receive from the governments of non-EU countries, as well as entities with significant legal, economic, organic, or decisional connections to a third country’s government.

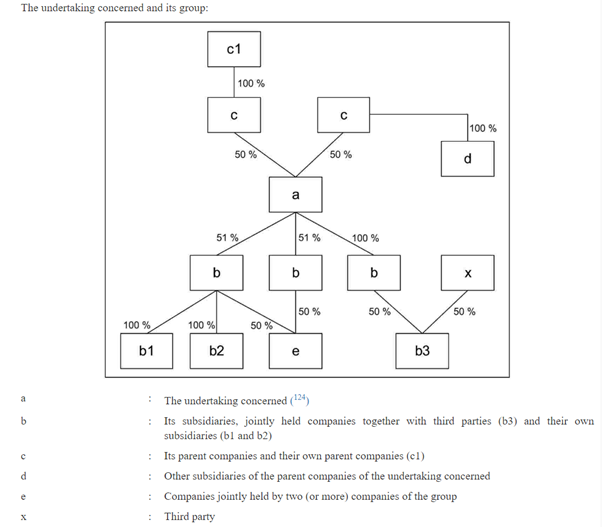

Calculation of thresholds

Under the FSR, the calculation of an undertaking’s turnover for the purposes of a notification of a concentration mirrors the methodology used under the EU’s Merger Control Regulation. Therefore, the relevant turnover is calculated by adding together the respective turnovers of the relevant undertaking, its subsidiaries, its holding companies, and the subsidiaries of its holding companies. If any of the aforementioned companies has joint control of another company alongside a third party, then only part of the jointly controlled company’s turnover should be included in the calculation of the undertaking’s turnover. Figure7 below illustrates which companies would be relevant when calculating the turnover of an undertaking.8

Figure 2: Notion of the undertaking concerned and its group

The approach is similar when calculating the FFCs received by the relevant undertaking, requiring each notifying party to aggregate all the FFCs it has received, alongside those received by its subsidiaries, holding companies, and the subsidiaries of its holding companies.9

For a notification of a public procurement bid, the relevant parties are different. As such, the calculation of whether the FFC notification threshold was reached for a public procurement bid must account for the FFCs received by the economic operator (the entity submitting the bid), as well as its subsidiaries without commercial autonomy, and its holding companies. In addition, the FFCs received by the economic operator’s main subcontractors and suppliers may need to be included if their participation is known at the time of submission of the notification and their participation ensures key elements of the contract performance. Their participation will be key where the economic share of their contribution exceeds 20 per cent of the value of the submitted tender.

It is important to remember that for the purposes of ascertaining whether the notification thresholds are met, all FFCs received by the relevant parties must be included, regardless of their type or value.

FSR procedure and fines

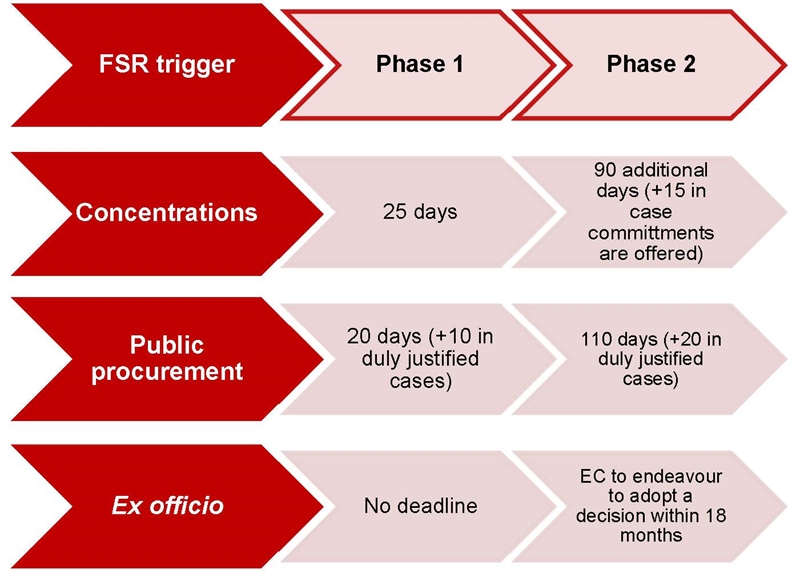

The timeline for a notification of a concentration under the FSR is deliberately aligned with the timeline under EU Merger Control rules. This means that the EC has 25 working days to review a notifiable transaction and an additional 90 working days (extendable by 15 working days in case commitments are offered) if it decides to open an in-depth investigation into the transaction. Intriguingly, the EC is not obligated to issue a decision under the first phase of the investigation. Therefore, if the EC does not open an in-depth investigation, a party can consider its concentration cleared under the FSR after the lapse of 25 working days from the EC’s receipt of a complete notification.

Notifications of participation in public procurement tenders are subject to a different timeline, which accounts for the involvement of a separate contracting authority handling the public procurement process. When submitting a tender or a request to participate in a public procurement procedure, bidders are required to notify the notifiable FFCs it received first to the relevant contracting authority or declare that they have not received any notifiable FFCs. Upon receipt of either the notification or the declaration, the contracting authority must forward them to the EC without delay, which will then have 20 working days (extendable by 10 working days) to decide whether to open an in-depth investigation from the date it receives a complete notification. If it opens an in-depth investigation, it must issue a decision within 110 working days after receipt of the complete notification (extendable by 20 working days).

Failure to notify either a notifiable concentration or a notifiable public procurement bid can lead to significant fines of up to 10 per cent of a company’s aggregate worldwide turnover. In addition, the EC has the power to prohibit the concentration or the award of the tendered contract if it finds that the notifying party in each case benefited from a distortive foreign subsidy.

There is no fixed timeline for an ex officio investigation. While the EC is bound to endeavour to adopt a decision within 18 months of opening an in-depth investigation, this is not a hard deadline, and investigations are likely to be drawn out.

Figure 3 below summarises the relevant timelines.

Figure 3: FSR timelines (figures are in working days)

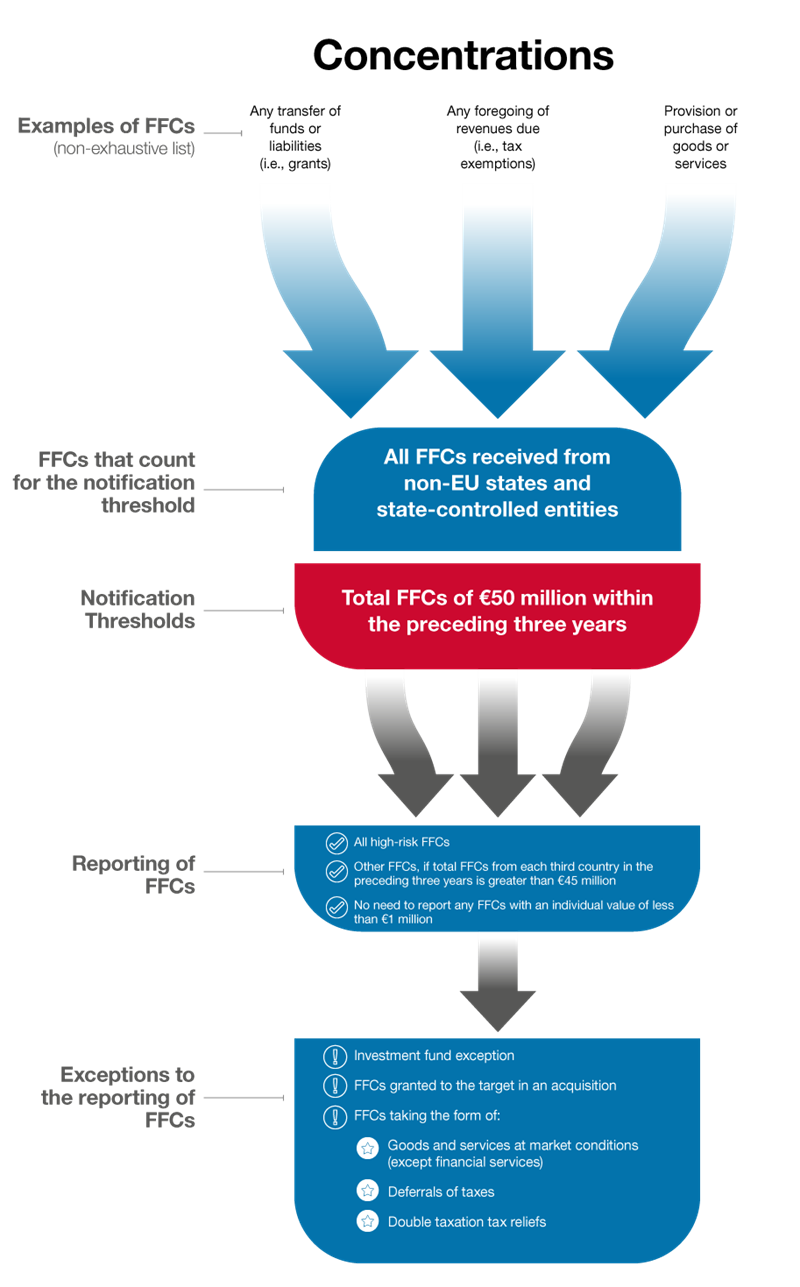

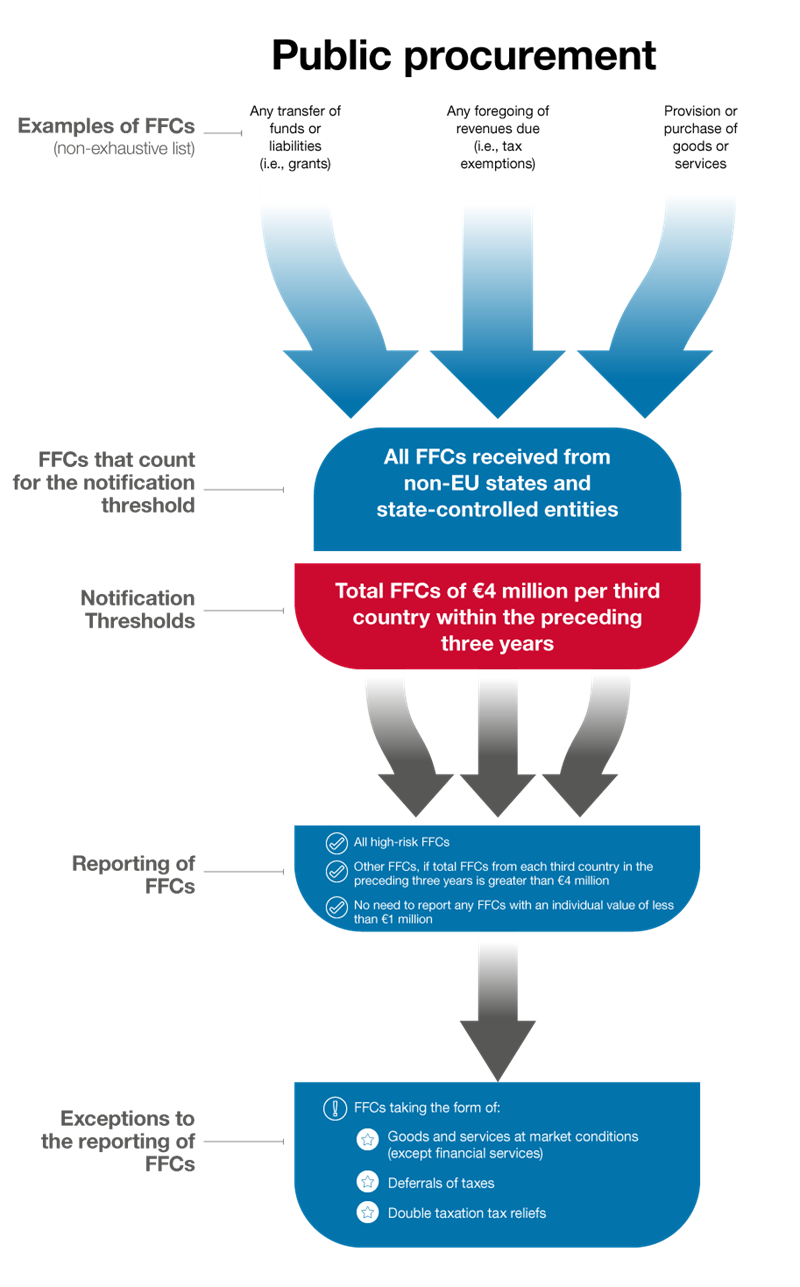

FSR reporting obligations

As set out above, the definition of financial contributions under the FSR is extremely wide. This definition remains unchanged by the FSR Implementing Regulation10 and will be applied for calculating whether the threshold to file has been met for a concentration or participation in a public procurement process.

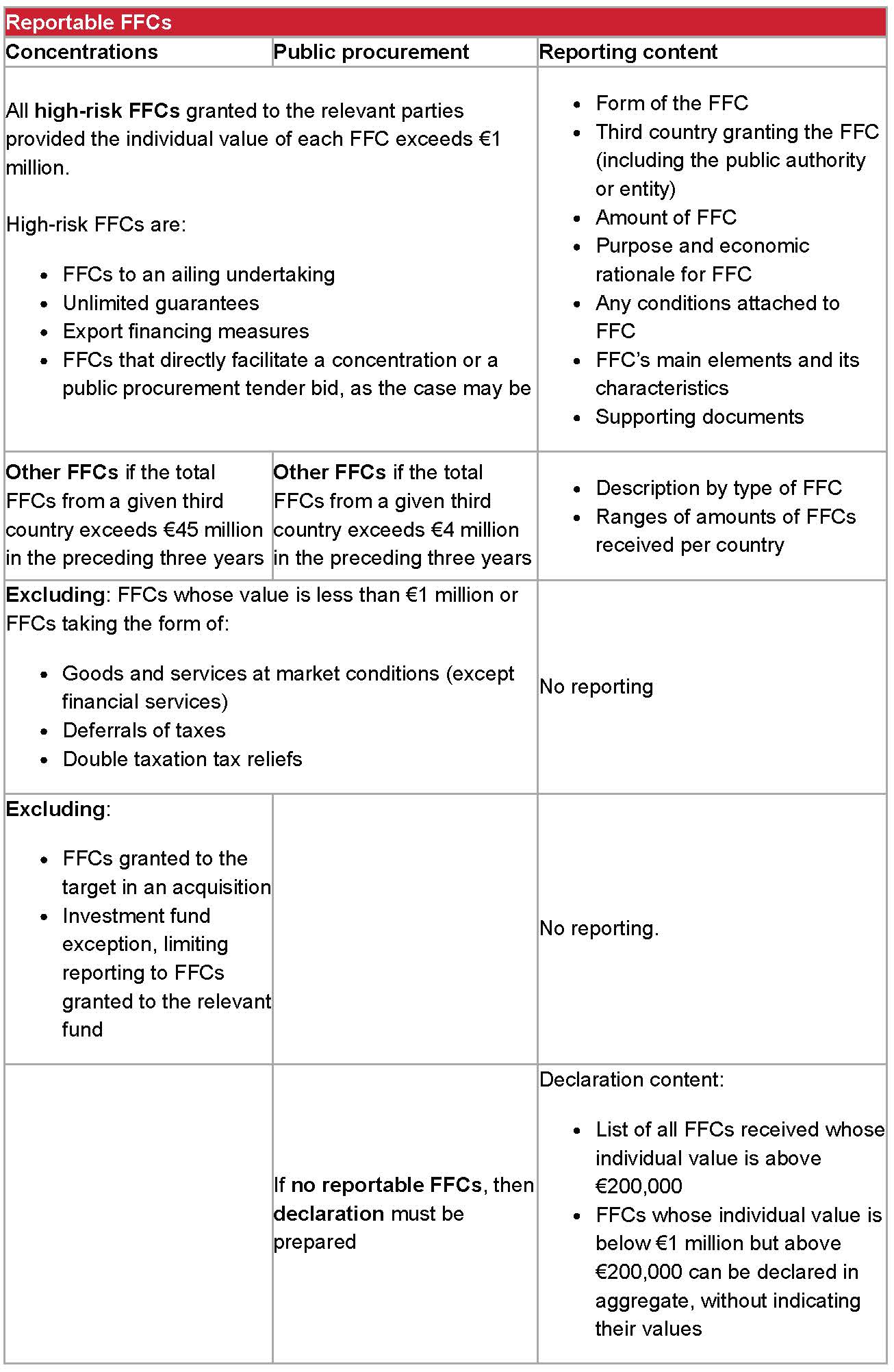

However, the EC has taken on board some of the feedback it received during its market consultation between February and March 2023. It reduced the onerous burden on businesses required to submit a notification under the FSR by narrowing down the scope of reportable FFCs that need to be included in the notification form. Therefore, FFCs can now be divided into three separate categories, depending on their risk level and their value.

Category 1: High-risk FFCs above €1 million

The parties are required to report detailed information for each FFC they received that is equal to or in excess of €1 million in the three years prior to the concentration or the tender bid, and that falls into certain categories of high-risk FFC categories. These high-risk categories are:

a. Contributions to an ailing undertaking

b. Unlimited guarantees

c. Export financing measures

d. Contributions that directly facilitate a concentration (in case the notification relates to a concentration) or contributions that directly facilitate a public procurement tender bid (in case of a public procurement notification).

The parties will have to provide information regarding the form of the financial contribution, the third country granting the FFC (including the public authority or entity), the amount of each contribution, the purpose and economic rationale for it, any conditions attached to it, its main elements, and its characteristics. The parties must also provide supporting documents regarding these high-risk FFCs alongside the notification.

Category 2: Other FFCs above €1 million

In relation to other types of FFCs, the relevant notification forms require that the notifying parties provide an overview of the FFCs equalling or exceeding €1 million received by the notifying parties over the past three years. Such FFCs must be grouped per non-EU country and per type (such as direct grant, loan, tax advantage, guarantee, risk capital instrument, equity intervention, debt write-off, contributions provided for non-economic activities), with a brief description needed for each FFC type.

The notifying parties must only include information regarding those countries where the estimated aggregate amount of all FFCs granted to the notifying parties in the three years prior to the concentration or public procurement tender bid (as the case may be) is:

- €45 million or more for concentrations or

- €4 million for public procurement tenders

The notifying parties must quantify the estimated aggregate amount of FFCs granted by each third country in the preceding three years, taking into account the high-risk FFCs referred to above, but excluding FFCs taking the form of:

- Provision or purchase of goods/services (except financial services) at market terms in the ordinary course of business, including goods or services purchased or provided following a competitive, transparent, and non-discriminatory tender procedure;

- Deferrals of payment of taxes or social security contributions, tax amnesties, and tax holidays, as well as normal depreciation and loss-carry forward rules that are of general application; and

- Application of tax reliefs for avoidance of double taxation.

The EC’s approach to the above forms of FFCs indicates the EC’s acknowledgement that these FFCs are highly unlikely to distort competition in the EU single market.

Category 3: FFCs below €1 million

The EC generally does not require that parties disclose any information regarding FFCs falling below €1 million in value, but such FFCs should be included when calculating whether the notification thresholds are met.

However, where the conditions for a notification of a public procurement bid are not met solely due to the aggregate FFCs received from any individual third country over the preceding three years being below €4 million, notifying parties must list in a declaration all the FFCs they received above a de minimis amount (currently set at €200,000) and confirm that these FFCs are not notifiable. FFCs received with a value below €1 million, but above the de minimis value in the preceding three years may be declared in aggregate, without indicating their individual values.

The EC may, on a case-by-case basis, request more detailed information on any FFC received by the parties, even if such FFC is below €1 million in value or falls within the exclusions outlined above (i.e., provision or purchase of products at market terms in the ordinary course of business, tax reliefs for avoidance of double taxation or tax deferrals, holidays, and amnesties of general application).

Valuing individual FFCs and timing

For the purposes of reporting and categorising each FFC received, businesses must value the individual FFCs they have received (i.e., to determine whether they are below €1 million, and hence not reportable) and determine when such FFCs were granted, to confirm whether they are within the preceding three years. In some cases, this may be a straightforward exercise, such as a direct subsidy grant in a single instalment. Other FFCs might require a more nuanced approach, such as FFCs in the form of contracts for the provision of services or FFCs whose value is not certain at the time of the notification.

The EC has provided some guidance on how to value FFCs and determine their timing. The EC clarified that FFCs must be assessed individually, without aggregating them per type or per country to assess whether the €1 million threshold is exceeded. The prevalent understanding is that this should be assessed on a per contract or scheme or entitlement basis (as the case may be), and not on a per payment basis. This is because, as the EC explained, the FFC will be considered granted from the moment the beneficiary obtains a legal entitlement to receive it. Therefore, the relevant moment in time to determine whether an FFC must be reported is the date on which the FFC is granted – not the date on which it is received.

In case of a contract for the provision of a service, the EC has drawn a distinction between contracts where remuneration is certain and contracts where the remuneration is conditional. Where the remuneration is certain, the relevant moment in time is the date on which the contract is signed. The entire amount of the remuneration will be considered as a granted FFC at that moment, regardless of whether this is paid out in instalments. However, in contracts where a third country purchases a service, and the right of the service provider to receive the different instalments of the remuneration is subject to the actual delivery of the services, the relevant moment in time to consider the FFC as granted to the service provider is the date when it is entitled to receive the remuneration (i.e., when the services are delivered). This means that conditional future instalments payable after the notification date should not be included in the calculation of the FFC’s value.

Where the value of an FFC is not clear – either because of the nature of the FFC or because the FFC may be undervalued – the EC will consult economists to calculate the market value of the FFC.

The investment fund exception

Another sign of the EC’s responsiveness to the feedback it received during the public consultation process comes in the form of the reporting exception for private equity funds in the notification form for concentrations. This exception was added to address the concerns of investment management companies regarding the potentially insurmountable administrative burden that such companies would face when collecting the relevant information for the large number of different funds and portfolio companies under their control. This exception only applies to the reporting of concentrations, but not tenders.

This exception allows investment funds that are subject to the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive11 (AIFMD) (or third-country equivalent legislation) to avoid reporting the FFCs granted to other investment funds managed by the same investment company, provided that:

a. The majority (more than 50 per cent) of investors in the notifying fund are different to the investors of other investment funds, measured according to their entitlement to profit, and

b. There are no or limited economic and commercial transactions between the notifying fund (including the companies controlled by this fund) and other investment funds (including the companies controlled by these funds).

The exception itself provides some guidance as to the economic and commercial transactions that may be relevant when considering whether the exception applies. As such, transactions between funds (and the companies controlled by such funds) regarding (but not limited to) the sale of assets or ownership in companies, loans, credit lines, or guarantees within the past three years would need to be disclosed to the EC, which will decide whether such transactions could be considered limited in nature. On the other hand, transactions at market terms in the ordinary course of business are unlikely to be considered enough to remove the benefit of the exception, but this will only be confirmed either during pre-notification discussions with the EC or once the EC develops its case practice.

The exception does not dispense with the need for single-fund investors to monitor, collect, and disclose information about FFCs received by their portfolio (group) companies (their subsidiaries), since these must be reported by the notifying fund. Importantly, this exception only applies to the reporting of low-risk FFCs. High-risk FFCs (as set out above) still need to be reported at the investment company level, including all funds and portfolio companies.

Figure 4: FSR reporting obligations

Practical guidance for FSR compliance

Businesses must prepare a system of information collection regarding financial contributions received from non-EU countries. They should ensure that their transaction planning accounts for the impact of the FSR across all transaction stages, from due diligence to conditions precedent and closing, while the planning of public procurement bids must also be amended to ensure that all the required information can be collected promptly and that deadlines will not be missed.

Businesses should closely monitor all financial contributions that they receive from non-EU states, as well as financial contributions from any entities that could be considered to be controlled by a foreign state. There might be arguments to exclude certain FFCs received from certain entities when it comes to the final notification, but the safest approach is to take these into account when preparing to report and then to discuss individual cases with the EC during the pre-notification stage, where any arguments to exclude individual FFCs can be raised.

The EC has clarified that the narrowing down of the scope of the reportable FFCs through the FSR Implementing Regulation has no effect on the calculation of whether an undertaking has reached the relevant notification threshold. Therefore, FFCs below €1 million or FFCs taking the form of an agreement to provide or purchase goods or services at market terms, a tax deferral, or a tax relief for the avoidance of double taxation must be included in the calculation of whether the FFCs received reach:

- The €50 million aggregate notification threshold for concentrations; or

- The €4 million per third country notification threshold for public procurement.

Hence, businesses must keep records of all FFCs that they receive, regardless of their value or type, to better assess their exposure to the FSR regime and be prepared in case of a notifiable M&A deal or a public tender in the EU.

For investment management companies, a pragmatic approach would be for each fund to collect the relevant information for the companies under its control and relay that information to the investment management company. The investment management company would then combine all the relevant information at the investment company level to calculate whether it meets the notification thresholds, and it would pass on information related to the thresholds and the high-risk FFCs received by other funds to the relevant notifying fund in each case.

Crucially, the EC has consistently stressed that it is available to discuss individual cases during pre-notification discussions with parties contemplating a potentially notifiable concentration or public procurement tender bid. During the pre-notification stage, the EC can provide guidance regarding the FFCs for which it will require additional information. Interested parties should make use of the ability to launch pre-notification discussions with the EC and adapt their envisaged timelines to account for such discussions.

Businesses should note the dichotomy between what counts as an FFC for the purposes of the notification threshold and which FFCs must be reported once the notification thresholds are met. Figure 5 below illustrates this dichotomy.

Figure 5: FFCs for notification and reporting purposes

Conclusion

The FSR adds another regulatory obstacle for international businesses operating in the EU, with extensive record-keeping procedures needed to ensure that all FFCs are monitored and tracked. However, a considerate and strategic approach to record-keeping will generally suffice to avoid any real impact on an enterprise’s business strategy, and the many uncertainties regarding the scope of the FSR will be resolved as the EC develops its case practice. The EC’s willingness to discuss with parties subject to a potential notification obligation is a valuable tool that should be used by businesses to clarify any outstanding questions.

- Regulation (EU) 2022/2560 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 December 2022 on foreign subsidies distorting the internal market.

- See sections (iv) and (v) below for more information on what FFCs are and how they are calculated.

- Council Regulation (EC) No. 139/2004 of 20 January 2004 on the control of concentrations between undertakings (the EC Merger Regulation).

- The EC may conduct inspections in the territory of a third country, provided that the government of that third country has been officially notified and raises no objection to the inspection. The EC may also ask the relevant parties to give their consent to the inspection.

- On 4 May 2023, Royal Excelsior Virton (“Virton“), a professional football club in Belgium’s second division, lodged a complaint against competing club SK Lommel alleging that SK Lommel has benefited from foreign subsidies from the U.A.E. which distorted the professional football market in the EU and, in particular, in Belgium (see official Virton statement in French and English). On 14 August 2023, La Liga, Spain’s top football division, lodged a complaint over foreign subsidies with the EC alleging that Paris Saint-Germain FC (PSG) has received Qatari investment that seriously distorts the internal market (see official statement).

- Fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory terms.

- Extract from para. 178, Commission Consolidated Jurisdictional Notice under Council Regulation (EC) No. 139/2004 on the control of concentrations between undertakings of 16 April 2008.

- The full turnover of the companies marked (a), (b), (c), (d), and (e) would be relevant for the calculation of the turnover of an undertaking. Only 50 per cent of the turnover of (b3) would be included, while the turnover of (x) should be fully excluded.

- The FSR diverges from the EU Merger Control Regulation when it comes to the apportionment of FFCs to joint ventures. While the turnover of a joint venture is apportioned equally among the venture partners under both the Merger Control rules and the FSR, FFCs are instead fully allocated to the joint venture, without any apportionment to account for the partial control of the joint venture. Therefore, all FCCs received by (a), (b), (b3), (c), (d), and (e) would be relevant.

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2023/1441 of 10 July 2023 on detailed arrangements for the conduct of proceedings by the Commission pursuant to Regulation (EU) 2022/2560 of the European Parliament and of the Council on foreign subsidies distorting the internal market.

- Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (2011/61/EU). The AIFMD regulates hedge funds, private equity, real estate funds, and other Alternative Investment Fund Managers (funds sold to professional investors), requiring them to obtain authorization and make various disclosures as a condition to operating. The European Securities and Market Authority keeps a central public register identifying each hedge fund, private equity firm, real estate fund, and other AIFM that is within the AIFMD’s scope, and that has been authorized under the AIFMD.

In-depth 2023-274