Key takeaways

- The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has followed the European Commission (EC) in adopting guidance dedicated to the application of competition rules to sustainability agreements.

- In contrast to the EC’s wide understanding of sustainability, which covers both environmental and wider social objectives, the CMA’s Green Agreements Guidance focuses solely on agreements pursuing environmental objectives.

- Environmental sustainability agreements are those aiming to prevent, reduce or mitigate the adverse impact of the parties’ activities on the environment or assisting with the transition towards environmental sustainability.

- The CMA specifically promotes climate change agreements, which contribute to combatting climate change, by making it easier for parties to prove the benefits of these agreements.

- The CMA will operate an open-door policy without eligibility conditions, enabling businesses to approach it with any questions they may have regarding its guidance. In contrast, businesses can only approach the EC for informal guidance if their agreement poses a novel or unresolved question, whose clarification would be in the public interest.

- While the two regimes have minor differences, the overarching message from both the CMA and the EC is that competition rules will not stand in the way of genuine collaboration in pursuit of environmental sustainability objectives.

On 12 October 2023, the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) published its Green Agreements Guidance, coming hot on the heels of the European Commission’s (EC) earlier adoption of a chapter dedicated to sustainability agreements in its updated Horizontal Guidelines on 21 July 2023. Both the CMA’s guidance and the EC’s guidelines address growing calls for a relaxation of competition rules to enable increased cooperation between competitors to achieve sustainability objectives.

The CMA’s guidance focuses solely on environmental sustainability agreements, specifically those aiming to prevent, reduce or mitigate the adverse impact of the parties’ activities on the environment or assisting with the transition towards environmental sustainability. The CMA also goes beyond the EC in its treatment of climate change agreements, which contribute to combatting climate change, by making it easier for companies to prove the benefits of such agreements. Despite the differences in the two regimes, the message from both the CMA and the EC is clear: competition rules should not prevent collaboration in pursuit of genuine ESG objectives.

(i) Scope

The CMA has diverged from the more expansive approach to sustainability that the EC has espoused. The notion of sustainability in the EC’s guidelines encompasses not only environmental protection, but also wider social objectives, such as the protection of human rights and promotion of labour rights. In contrast, the CMA’s guidance focuses solely on environmental sustainability agreements, and promotes, in particular, agreements focusing on climate change. Examples of environmental sustainability agreements include agreements between competitors to reduce the use of pesticides, stop the use of microplastic polluting materials, or increase recycling rates. Climate change agreements are a sub-set of environmental sustainability agreements and include agreements reducing the negative externalities of the greenhouse gases emitted from the production, distribution or consumption of the relevant products, such as an agreement between manufacturers of a product to phase out a highly emitting production process, or an agreement between delivery companies to switch to using only electric vehicles.

The CMA noted that its narrower focus is warranted due to the scale and urgency of the challenge to ensure environmental sustainability, and especially to combat climate change. Businesses have an important role to play in meeting the UK’s climate targets, with industry collaboration being key to this. Hence, the CMA clarifies, through its guidance, that where collaboration between competitors is needed to promote environmental sustainability, competition rules will not stand in their way.

The CMA clarified that other types of sustainability agreements are out of scope of its Green Agreements Guidance, but these can be examined under its general Guidance on Horizontal Agreements. As such, these agreements could nonetheless be considered compliant with UK competition law after an effects-based assessment, whereby the agreement’s benefits will be assessed against any harm it causes to competition. Therefore, it is expected that the CMA’s effects-based assessment of non-environmental sustainability agreements will likely not result in markedly different outcomes than those expected under the EC’s Horizontal Guidelines.

(ii) Agreements unlikely to infringe competition law

The CMA Green Agreements Guidance and the sustainability agreements chapter in the EC’s Horizontal Guidelines have a similar structure, setting out their respective scope before considering which agreements are unlikely to raise competition effects. The EC’s Horizontal Guidelines only provide four examples of such agreements, though these examples are non-exhaustive and other types of sustainability agreements may also be considered as having no anti-competitive effects under EU competition law.

The examples set out in the EC’s guidelines are agreements:

a. Relating solely to the internal corporate conduct of businesses (e.g., elimination of single-use plastics from business premises or temperature control in corporate premises).

b. Relating to the planning of industry-wide campaigns to raise awareness of sustainability issues within the industry.

c. Setting up a joint database containing general information regarding the sustainability (or lack thereof) of their suppliers, producers or distributors, provided that there is no obligation to exclusively contract with sustainable entities or cease contracting with unsustainable entities.

d. Solely aiming to ensure compliance with an international law which is not fully implemented or enforced by a signatory state to that law.

The CMA’s approach is more expansive on this, reiterating the above examples, while providing the following additional examples of agreements unlikely to raise competition concerns:

a. Non-appreciable agreements, where the parties have a very small combined market share of the affected market (below 10%), and the agreement does not contain by-object restrictions of competition, such as market sharing or price setting. This is primarily intended to help small and medium-sized enterprises.

b. Agreements to pool funds for mitigating, adapting to or compensating for the effects of greenhouse gas emissions generated in production.

c. Joint lobbying agreements for policy or legislative changes, provided that these are not used to exclude a competitor by lobbying a standard-setting body in a way that controls the standard-setting process.

d. Agreements to do something jointly which none of the parties could do individually due to, for example, the level of risk involved or the level of investment required, provided that the businesses involved could not have proceeded using a form of cooperation that is less restrictive of competition. This could cover early-stage scientific or technological research with an environmental sustainability objective.

e. Agreements setting non-binding industry-wide targets or ambitions, such as targets to reduce the whole industry’s CO2 emissions, provided that the participating businesses are free to independently determine their own contributions and the way in which they will meet these targets or ambitions.

f. Agreements to phase out or withdraw non-sustainable products or processes, provided that there is no appreciable impact on price, quality or choice, and it does not have the object of eliminating competitors or market sharing.

g. Agreements between shareholders to vote in favour of corporate policies that pursue environmental sustainability or against policies that do not.

(iii) Sustainability standards

In a sign of the developing importance of sustainability standards, both the CMA and the EC provide a soft safe harbour for agreements setting sustainability standards aimed at making products or processes more sustainable. Sustainability standardisation agreements usually oblige competitors to adopt and comply with certain sustainability standards, often requiring compliance with sustainability metrics, such as CO2 emissions or recycling rates. Agreements meeting the requirements of the soft safe harbour are unlikely to breach competition law, though both the CMA and the EC retain the ability to intervene in cases where the anti-competitive effects of such an agreement nonetheless outweigh its benefits.

The requirements for the application of the safe harbour are largely aligned under both regimes. As such, both the CMA and the EC require that:

a. Sustainability standards must be transparent, with all interested competitors able to participate in the selection of the standards.

b. Companies that do not wish to participate in the standards should not be hindered from continuing to supply the market.

c. Participants must remain free to adopt higher sustainability standards.

d. The outcome of the standard-setting process must be non-discriminatory and accessible to all interested competitors, even after their initial adoption.

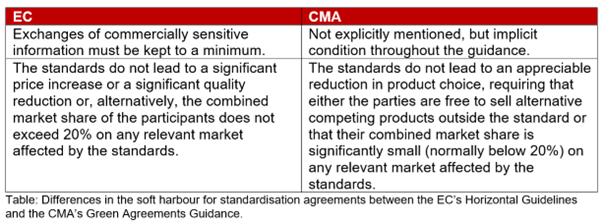

In addition, the EC requires that exchanges of commercially sensitive information are kept to a minimum, and that the standards do not lead to a significant price increase or a significant quality reduction, or alternatively that the combined market share of the participants does not exceed 20% in any relevant market. However, instead of the EC’s emphasis on avoiding an increase in prices or a reduction in quality, the CMA primarily focuses on preventing a reduction in product choice. As such, a standard-setting agreement will be compliant with UK competition law if the participating businesses can sell alternative competing products that do not meet the standards or, alternatively, if the combined market share of the parties is sufficiently small. The CMA indicates that a market share below 20% will normally be sufficiently small, but this is a flexible threshold, contrary to the EC’s guidelines, which mandate that the 20% market share must not be exceeded.

While there is no explicit requirement to limit exchanges of information in the CMA’s guidance regarding standard-setting agreements, this is nonetheless an implicit condition embedded throughout the guidance. This requires that any information shared between the parties does not go beyond what is objectively necessary to implement the agreement, and is proportionate to its objectives.

(iv) Effects-based assessment

Sustainability standardisation agreements falling outside the soft harbour set out above, and agreements that have anti-competitive effects, may nonetheless be compliant with competition law if their benefits outweigh their competitive harm. As such, both the CMA and the EC set out similar guidance on the application of the general effects-based assessment, whereby the benefits of an agreement are assessed against the harm it causes to competition, requiring that the agreement:

a. leads to demonstrable efficiency gains;

b. does not substantially eliminate competition;

c. only imposes restrictions on competition which are indispensable to the agreement’s objectives; and

d. bring benefits which are passed on to consumers.

Crucially, both regimes generally require that the consumers in the affected markets receive a fair share of the benefits. Such benefits can be direct or indirect and can accrue both in the present and in the future. The quantification of future benefits will depend on the nature of the agreement and the claimed benefits. Collective benefits – those benefitting a wider section of society than just the relevant consumers – are also relevant in this assessment, provided that their beneficiaries substantially overlap with the consumers in the relevant markets.

The only point of divergence between the CMA’s guidance and the EC’s guidelines on the application of the effect-based assessment comes in the form of the added leniency for climate change agreements. The CMA’s effects-based assessment of climate change agreements will take into account the full climate change benefits of the agreement to all UK consumers, without the need for the beneficiaries of these benefits to substantially overlap with the consumers in the relevant market. This greatly facilitates the use of climate change agreements, as the parties to such an agreement only need to demonstrate that:

a. the agreement’s climate change benefits are in line with, or exceed, existing legally binding requirements or well-established national or international targets (including climate change goals in international treaties);

b. UK consumers in general benefit from the agreement; and

c. these benefits outweigh the harm caused by any restrictions included in the agreement.

(v) Open-door policy and qualified immunity from fines

The CMA acknowledges that it will not always be clear how to distinguish between climate change and general environmental benefits, but it reminds interested parties of the CMA’s open-door policy, whereby such parties can approach the CMA for informal guidance on this, and any other questions that parties may have on the application of the Green Agreements Guidance. The EC has taken a similar approach, encouraging interested businesses to approach it for informal guidance, but it limits the cases where informal guidance may be sought to only those where the sustainability agreement poses a novel or unresolved question, whose clarification would be in the public interest. No such requirements exist under the CMA’s Green Agreements Guidance, illustrating the CMA’s intention to be more actively involved in guiding interested parties. Additionally, as well as the parties to an agreement, NGOs and trade associations can approach the CMA for informal guidance, in contrast to the EC’s regime under which only the parties to an agreement can request such guidance.

The incentive for interested parties to contact the regulators in case of any questions is enhanced by the commitment of both the CMA and the EC to not issue any fines for agreements that were discussed with the regulators and in respect of which either no concerns were raised, or any concerns raised were addressed by the parties. This qualified immunity from fines only remains in play to the extent that the parties provided accurate information and did not withhold any relevant information from the regulators. Importantly, the CMA expects parties to an agreement that has been subject to the CMA’s informal guidance to monitor the agreement’s compliance with UK competition law, particularly in light of the CMA’s continued informal guidance issued in connection with its Green Agreements Guidance.

Both regulators have committed to publishing the results of the informal guidance process, albeit in redacted form, to provide added clarity on the application of the relevant rules. Therefore, interested parties should note that details of their agreements may be made public through either the publication of the EC’s guidance letter, or the CMA’s publication of a summary of the agreement, together with an assessment of its risks and solutions.

(vi) Impact on business

Despite the apparent differences in the two regimes, the overarching message from both the CMA and the EC is that sustainability agreements, in particular environmental sustainability agreements, are to be encouraged, especially where they have no or limited impact on competition. Both the CMA’s Green Agreements Guidance and the EC’s Horizontal Guidelines on sustainability agreements are valuable additions to an increasingly complex regulatory regime, clarifying that ESG-conscious businesses can, in most cases, pursue their environmental sustainability objectives in collaboration with competitors.

In-depth 2023-267