Taxpayers may be able to extend their NOL carryover period by up to six years

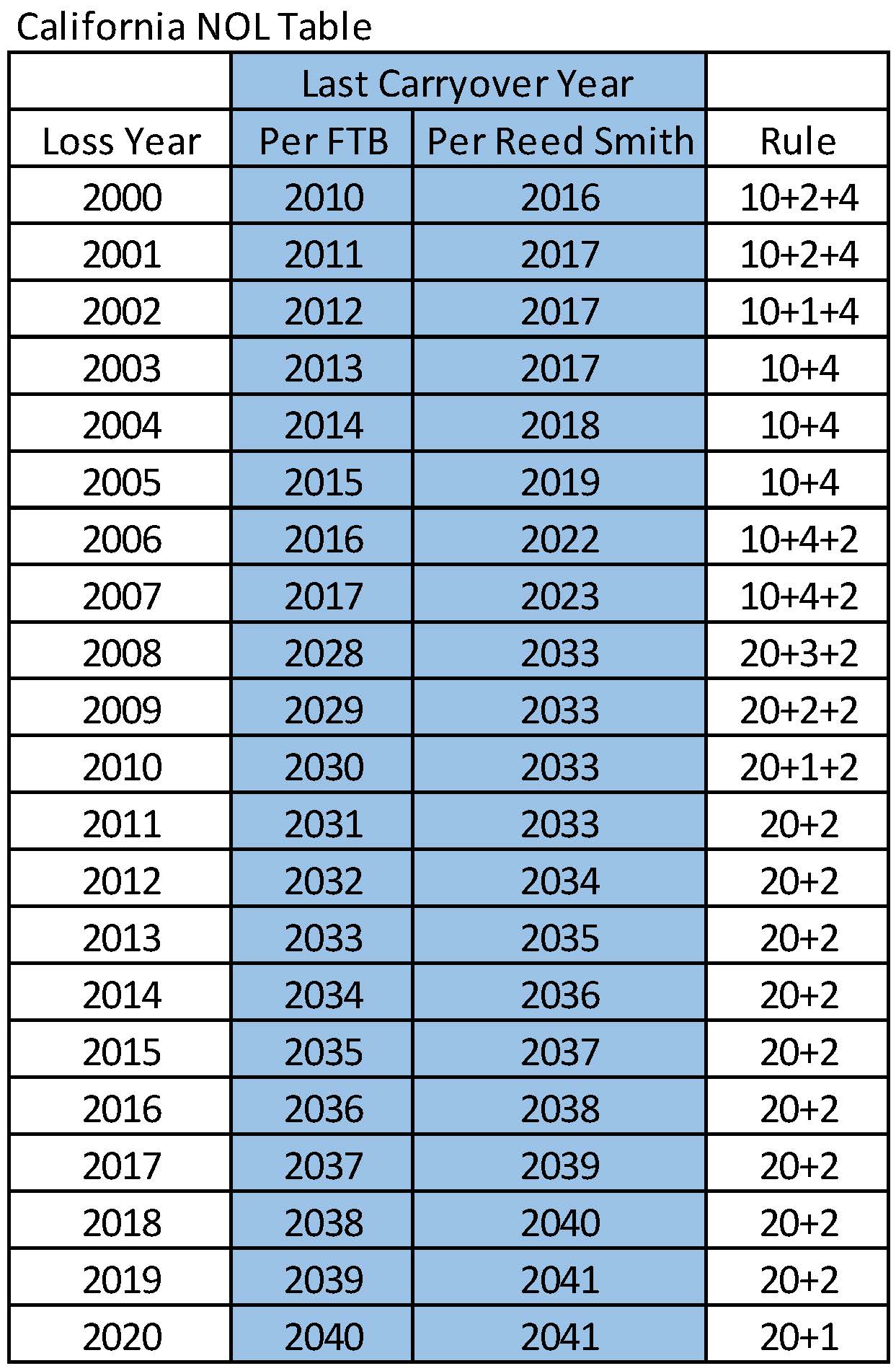

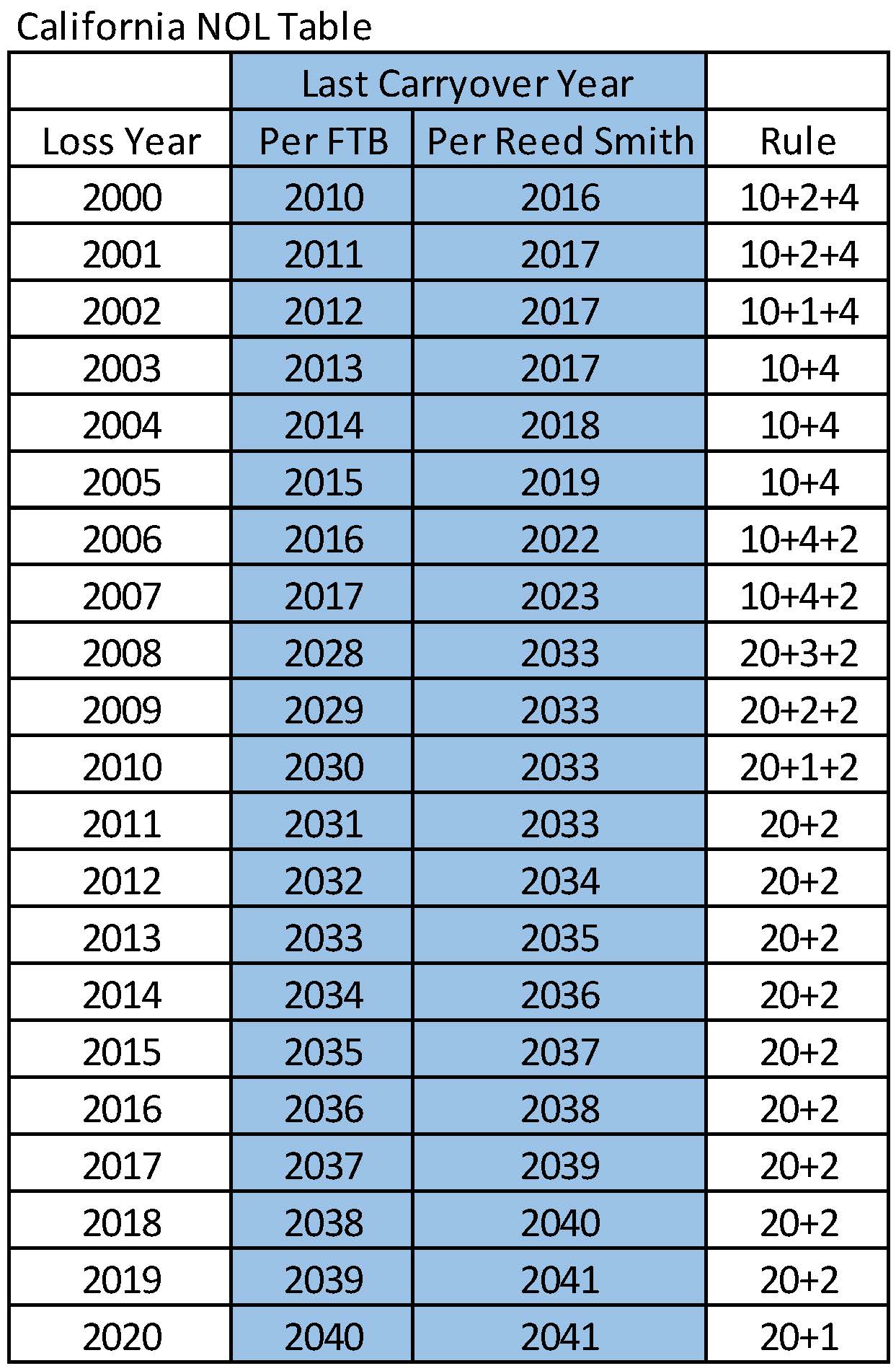

In California, the standard rule for NOL carryovers is that they can be carried forward for 10 years1 following the loss year for losses generated in 2000 through 2007 and for 20 years following the loss year for losses generated in 2008 and forward.2 However, as a part of the state’s 2002-2003 budget, California suspended the utilization of NOLs for tax years 2002 and 2003 and extended the carryover periods by one year for losses incurred in 2002 and two years for losses incurred before 2002.3 Then as part of the state’s 2008-2009 budget, the NOL deduction was suspended for tax years 2008 through 2009.4 A couple years later, as a part of its 2010-2011 budget, California extended the suspension of the NOL deduction through 2011.5 Although the legislature disallowed NOL deductions for the 2008-2011 years, similar to the 2002-2003 NOL suspension, the 2008-2011 NOL suspension was supposed to be just a matter of timing. The carryover period for NOLs suspended for tax years 2008 through 2011 was extended by four years for losses incurred in years prior to 2008, by three years for losses incurred in 2008, by two years for losses incurred in 2009, and by one year for losses incurred in 2010.6

In 2020, the California legislature once again turned to NOL suspensions, this time to combat projected budget deficits resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic.7 As a part of the state’s 2020-2021 budget, California suspended the use of NOLs for taxable years 2020 through 2022. Similar to the earlier suspensions, California extended the carryover periods by three years for losses incurred in taxable years before 2020, two years for losses incurred in 2020, and one year for losses incurred in 2021.8 Because the California legislature shortened the suspension to allow NOL deductions in 2022, the extension to the carryover periods is now two years for losses incurred in taxable years before 2020 and one year for losses incurred in 2020.

While the extended carryover period rules appear straightforward, the Franchise Tax Board’s (“FTB’s”) position is that a taxpayer is not afforded an extended carryover period unless the NOL deduction would have produced a tax benefit were it not for the suspension.9 Under Legal Ruling 2011-04, the taxpayer must essentially “test” each NOL carried into the suspension period. If the NOL would have produced a tax benefit in the suspension period, were it not for the suspension, the carryover period for that NOL is extended. If not, the NOL is not extended. In other words, the taxpayer must have sufficient income in the suspension year so that it could have used the NOL, were it not for the suspension, in order to extend the NOL.

The FTB’s “tax benefit/income testing” limitation on the statutory NOL extension provisions is invalid because:

- The “tax benefit/income testing” limitation is not authorized by, and conflicts with, the plain language of the statute; and

- The “tax benefit/income testing” limitation is contrary to the legislative intent of the statute, because the legislature intended that the suspension be purely a timing shift to address budget shortfalls.

Thus, the carryover period of California NOLs carried forward into the suspension years should be extended as follows:10

Taxpayers should also consider using this approach for purposes of valuing their deferred tax assets related to California NOLs.

California NOLs should be carried over and deducted on a combined group basis

California requires affiliated corporations conducting a unitary business to file a combined report, thus treating a group “as an integral unit in an entire business comprising the parent and all of its subsidiary corporations.”11 If a business is conducted in more than one legal entity, the state “look[s] at the total income of the group.”12 Therefore, although the statute imposes tax on “every corporation doing business” in California,13 the tax itself is computed as if a unitary group of corporations were a single entity.

The method of computing income of corporations within a unitary group also applies when computing losses of the members of the group. Thus, consistent with the theory of a unitary business, if a corporation is a member of a unitary group, an NOL is generated if the group’s deductions exceed the group’s gross income. The FTB agrees with this proposition. Thus, it follows that if the NOL is defined by reference to a group’s deductions and gross income, the resulting carryover and deduction should be made against the group’s gross income in a succeeding year. ndeed, the business income from all activities of a unitary business is combined into a single combined report, whether activities are conducted by divisions of a single corporation or by members of a commonly controlled group of corporations.14

While income and losses are computed at the unitary combined group level, regulation 25106.5(e) of the California Code of Regulations explicitly computes an NOL at the corporate member level. It does so based on a reading of Revenue and Taxation Code section 25108, which removes any context from its definition of “net operating loss.” That section defines the NOL deduction for a unitary group engaged in a multistate business. Section 25108 uses the singular term to refer to the taxpayer (“the corporation” or “that corporation”). But that singular term reflects a singular unitary group unit – not a particular legal entity within a unitary group. Thus, under section 25108, a group’s net loss should be deductible against the group’s net income.

This interpretation makes sense because:

- This method is consistent with the California legislature’s intent:

- There is no indication in the statute that the legislature intended for NOLs generated by a unitary group as a whole to be deductible only by certain members of the group. To the contrary, when California’s tax agencies have adopted a position contrary to unitary theory, the legislature has stepped in to correct that position.15

- This method is consistent with both the unitary business principle and the policy principles behind an NOL deduction:

- The unitary business principle “is a principle of taxation in which several elements of a business are treated as one unit for taxation purposes, with the goal of achieving a fair valuation.”16 Moreover the principle behind an NOL is to “permit a taxpayer to set off its lean years against its lush years, and to strike something like an average income computed over a period longer than one year.”17

Thus, we think California NOLs generated by a combined group should be carried over and deducted on a combined group basis.

Pre-2013 NOLs should be recomputed using a single-sales factor apportionment formula

After over 70 years of apportioning income using a formula based upon property, payroll, and sales, California, by voter initiative, adopted a sales-factor-only apportionment formula beginning with the 2013 tax year.18 As a result, taxpayers carrying pre-201319 NOLs, which were apportioned using a three-factor apportionment formula, into single-sales factor years are encountering an apportionment method mismatch which may be distortive. This mismatch causes the NOL deduction to fail its purpose of “strik[ing] something like an average income computed over a period longer than one year.”20

For taxpayers deducting pre-2013 NOLs, a solution to this mismatch would be to request alternative apportionment under section 25137, seeking permission to apportion the pre-2013 NOLs using the same single-sales factor formula used to apportion the income against which the losses are being deducted.

Conclusion

Given the early termination of the California 2020-2022 NOL suspension, allowing taxpayers to utilize NOLs for the 2022 tax year,21 taxpayers should consider reviewing their NOL schedules to determine if they can benefit from a longer carryover period, utilizing their NOLs on a combined group basis, and/or computing their pre-2013 NOLs using a single-sales factor apportionment formula.

In-depth 2023-022

- Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code § 24416(e)(1)(B). Effective January 1, 2016, Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code § 24416.20, which replaced formerly repealed Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code § 24416, was renumbered as Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code § 24416.

- Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code § 24416.22.

- Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code § 24416.3.

- Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code § 24416.9.

- Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code § 24416.21. As a result of S.B. 858, Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code § 24416.9 was repealed and the provisions set forth therein were generally moved to Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code § 24416.21.

- Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code § 24416.21(b).

- California Budget Summary: May Revision, Introduction, May 14, 2020.

- Cal. Rev. & Tax Code § 24416.23(b).

- California FTB Legal Ruling 2011-04, September 23, 2011.

- The table reflects the extended carryover period under current law.

- Edison Cal. Stores v. McColgan, 30 Cal. 2d 472, 475 (1947).

- Container Corp. of Amer. v. FTB, 117 Cal. App. 3d 988, 994 n. 3 (1st App. Dist. 1981) aff’d 463 U.S. 159 (1983).

- Cal. Rev. & Tax Code § 23151(a).

- Cal. Code Regs. § 25106.5(b)(2); California FTB Publication 1061, Guidelines for Corporations Filing a Combined Report (2015).

- For example, after the agencies flip-flopped regarding whether the throw-back rule should be applied on the basis of the activity of the entire unitary group, the legislature amended section 25135 to make it clear that throw-back must be applied on a group-wide basis. See Cal. Rev. & Tax § 25135(b) added by Act of February 20, 2009, ch. 10, § 12, 2009 Cal. Legis. Serv. 3rd Ex. Sess. Ch. 10 (A.B. 15) (legislatively adopting Finnigan).

- See Tenneco West, 234 Cal.App.3d at 1518 (emphasis added).

- See Libson Shops, Inc. v. Kohler, 353 U.S. 382, 386 (1957) (“Those [net operating loss carryover and carryback] provisions were enacted to ameliorate the unduly drastic consequences of taxing income strictly on an annual basis. They were designed to permit a taxpayer to set off its lean years against its lush years, and to strike something like an average income computed over a period longer than one year.”).

- Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code § 25128.7.

- Taxpayers were able to make an election to utilize the single-sales factor apportionment formula for the 2011 and 2012 tax years, however, some taxpayers failed to take the election.

- Libson Shops, Inc. at 386.

- California Budget Summary: Governor’s Budget, January 10, 20