Authors

Authors

Takeaways

The proposed Draft Guidelines highlight characteristics of certain mergers that the Agencies will more heavily scrutinize, such as mergers that increase the risk of coordination or involve partial ownership or minority interests. Consistent with the policies of the Agencies under the Biden administration, the Draft Guidelines signal increased review and enforcement actions of mergers in the Big Tech, private equity, and labor markets. While not explicitly singled out, many of the above principles are particularly relevant to big tech and private equity, such as mergers involving digital markets and platforms, serial acquisitions by allegedly dominate firms, and mergers in already concentrated markets. The Draft Guidelines call special attention to the labor market, with a specific emphasis on whether a reduction in labor market competition lowers wages or worsens employee working conditions. Though designed to transform competition enforcement, we also see the Draft Guidelines as an opportunity to engage in an open dialogue with the Agencies regarding potential procompetitive justifications for mergers that might not have been possible under prior guidelines.

It is important to note that these Draft Guidelines are not yet final; over the next 60 days, the Agencies will solicit comments from the public. Reed Smith is here to help you consider and prepare those comments. Please do not hesitate to reach out to our global antitrust and competition team, or the Reed Smith lawyer with whom you regularly work.

Thirteen principles:

1. Mergers should not significantly increase concentration in highly concentrated markets.

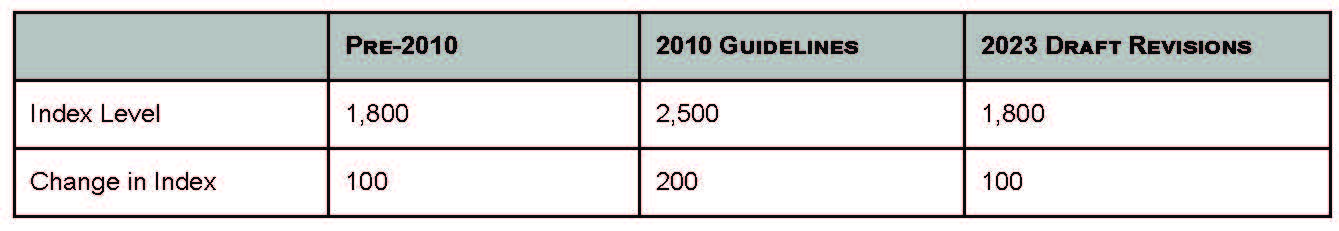

Concentration refers to the number and relative size of rivals competing to offer a product or service to a group of customers. The Agencies examine whether a merger between competitors would significantly increase concentration and result in a highly concentrated market. If so, the Agencies presume that a merger may substantially lessen competition based on market structure alone. The Agencies measure concentration levels using the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) whereby the higher the index, the more concentrated a market, and the larger the change in the index due to the merger, the more likely it might be to cause harm. In 2010, the Agencies increased the HHI thresholds at which they would consider a market “highly concentrated” as well as what change in the index driven by the merger would be cause for concern, effectively allowing more mergers to proceed. The revised Draft Guidelines restore both values to the pre-2010 lower threshold levels, signaling that fewer mergers will survive scrutiny by the Agencies.

2. Mergers should not eliminate substantial competition between firms.

If evidence demonstrates substantial competition between the merging parties prior to the merger, the Agencies can determine that the merger may substantially lessen competition, particularly where market shares do not reflect the competitive significance of the merging parties to one another. The Agencies consider the following factors that indicate substantial competition.

- Strategic deliberations or decisions: One firm monitoring the other firm’s pricing, products, marketing campaigns, output, and innovation plans can provide evidence of competition, whereby the firms react by taking steps to increase the competitiveness or profitability of their own products or services.

- Prior merger, entry, and exit events: Relevant mergers, entry, expansion, or exit events shed light on the presence of direct competition.

- Customer substitution: The more willing customers are to switch between two firms’ products, the closer competitors they are.

- Impact of competitive actions on rivals: The Agencies can also evaluate the level of competition by considering whether a firm’s competitive actions result in lost sales for the rival and the extent of the lost sales.

3. Mergers should not increase the risk of coordination.

A merger may substantially lessen competition when it results in the risk of coordination among the remaining firms in the relevant market, or when it makes existing coordination more effective. Coordination can occur in relation to price, product features, customers, wages, benefits, or geography, and can occur explicitly (e.g., collusive agreements not to compete) or tacitly (e.g., though observation and response to rivals’ actions). To assess whether mergers increase the risk of coordination, the Agencies consider three primary factors and several secondary factors.

A. Primary factors: Post-merger market conditions are more susceptible to coordination if any of the following are present: (1) a highly concentrated market; (2) prior actual or attempted attempts to coordinate; and (3) the elimination of or changes in the incentives of a firm with a disruptive presence in a market.

B. Secondary factors: (1) market concentration (coordination becomes more likely as concentration increases, even if it does not rise to the level of a “highly concentrated” market); (2) market transparency (a market is more susceptible to coordination if a firm’s behavior can easily be observed by its rivals, such as through public announcements); (3) competitive responses (coordination is more likely if a firm’s prospective competitive reward for attracting customers away from its rivals will be significantly diminished by the likely responses of those rivals); (4) aligned incentives (removing a firm that has different incentives from most others in a market can increase the risk of coordination); and (5) profitability or other advantages of coordination for rivals (coordination is more likely when firms have more to gain from coordination, such as great profitability).

4. Mergers should not eliminate a potential entrant in a concentrated market.

The Agencies examine whether, in a concentrated market, a merger would (a) eliminate a potential entrant by examining whether one or both of the merging firms had a reasonable probability of entering the relevant market other than through an anticompetitive merger, by reviewing evidence such as size and resources to enter, and whether such entry offered “a substantial likelihood of ultimately producing deconcentration of [the] market or other significant procompetitive effects”; or (b) eliminate current competitive pressure from a perceived potential entrant by determining whether a current market participant could reasonably consider one of the merging companies to be a potential entrant and whether that potential entrant has a likely influence on existing competition.

5. Mergers should not substantially lessen competition by creating a firm that controls products or services that its rivals may use to compete. When a merger involves products or services that rivals use to compete, the Agencies examine the merged firm’s ability to control access to those products or services to substantially lessen competition and whether they have the incentive to do so. A merger that gives the merged firm access to competitively sensitive information could undermine a rivals’ incentive to compete aggressively or could facilitate coordination.

6. Vertical mergers should not create market structures that foreclose competition.

In vertical mergers, the Agencies will conduct an analysis of how a merger would restructure a vertical supply or distribution chain. If the foreclosure share is above 50 percent, that factor alone is a sufficient basis to conclude that the effect of the merger may be to substantially lessen competition. Below a 50 percent share, the Agencies consider several plus factors to determine whether a vertical merger is likely to restrict options along the supply chain, including whether there is a trend toward further vertical integration, the nature and purpose of the merger, whether the relevant market is already concentrated, and whether the merger raises barriers to entry by limiting independent sources of supply.

7. Mergers should not entrench or extend a dominant position.

The Agencies will evaluate whether one of the merging firms already has a dominate position by considering whether (a) there is direct evidence that one or both merging firms has the power to raise prices, reduce quality, or otherwise impose or obtain terms that they could not obtain but for that dominance, or (b) one of the merging firms possesses at least 30 percent market share. The Agencies also evaluate whether the merger may entrench or extend that dominant position by behavior that lessens competitive threats, such as increasing switching costs.

8. Mergers should not further a trend toward concentration.

If market concentration “has been recently increasing,” the Agencies examine whether the merger would further that trend by evaluating the following two factors: (a) whether the merger is occurring in an industry that has a tendency toward concentration, which can be shown by market structure or other relevant market characteristics; and (b) whether the merger would increase the existing level of concentration or pace of that trend.

9. When a merger is part of a series of multiple acquisitions, the Agencies may examine the whole series.

If a firm engages in multiple acquisitions in related lines of business, the Agencies will evaluate the cumulative impact of such behaviors even if no single acquisition would risk violating antitrust laws. The Agencies do this by examining both the firm’s history of acquisitions (whether consummated or not) as well as current and future strategic incentives.

10. When a merger involves a multi-sided platform, the agencies examine competition between platforms, on a platform, or to displace a platform. Platforms provide different products or services to two or more different groups or “sides” that may benefit from each other’s participation. The Agencies protect competition between platforms by preventing the acquisition or exclusion of other platform operators that may substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly. The Agencies protect competition on a platform in any markets that interact with the platform. The Agencies protect competition to displace the platform or any of its services. The Agencies will examine all three of these aspects to determine whether they may substantially lessen competition.

11. When a merger involves competing buyers, the agencies examine whether it may substantially lessen competition for workers or other sellers.

The Agencies put a specific focus on labor markets where workers face a risk that a merger would substantially lessen competition for their labor. Because the employers are the buyers of labor, and workers are the sellers, a merger between employers may result in lower wages for workers or a decrease in the quality of benefits and working conditions.

12. When an acquisition involves partial ownership or minority interests, the agencies examine its impact on competition.

Acquisitions resulting in less than full control of an entity may still give the investor rights and decision-making power in the target entity, such as rights to appoint board members. The Agencies will analyze post-acquisition relationships in these situations to determine whether the acquisition may substantially lessen competition.

13. Mergers should not otherwise substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly.

The Guidelines are not exhaustive of the ways that a merger may substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly.

In-depth 2023-161

Authors