Key takeaways

- Historically, the European Commission (EC) would only review transactions under its merger control rules if the parties’ respective turnover met the EU merger control jurisdictional thresholds, unless transactions falling below these thresholds were referred to the EC by Member States under the so-called ‘Article 22 referral mechanism’.

- This mechanism can be activated if a transaction affects trade between Member States and can significantly affect competition within the territory of the referring Member States.

- Prior to 2021, this referral mechanism had not been used to review transactions falling below the national merger control thresholds of the referring Member States. However, in 2021, the EC updated its relevant guidance to encourage referrals of transactions where, despite the target’s turnover being below the national thresholds at the time of the acquisition, the target could develop into a significant competitive force in the future.

- Two recent referrals of mergers from Member States to the EC are clear signs of the EC’s increased appetite to examine mergers that are below both EU and national notification thresholds. Proactive and upfront engagement with competition authorities may be needed to assess the risk of referral.

- Under the referral procedure, mergers may be examined even after their completion. To further compound matters, the EU’s General Court recently held that, in certain circumstances, an ex post investigation of a merger is also possible under the abuse of dominance rules.

- Antitrust risk analysis of transactions is now subject to greater uncertainty, and businesses must, more than ever, carefully consider the antitrust implications of their transactions, even when these do not meet any notification thresholds.

- Parties should consider the risk of a referral or an ex post investigation of their transactions and account for this in their deal planning and transaction documentation.

Traditionally, parties to an acquisition did not have to concern themselves with merger control if they were able to establish that the relevant jurisdictional thresholds triggering merger control were not met. This has now changed, with the European Commission (EC) seemingly shedding its reluctance to examine below-thresholds concentrations and recently accepting two new referral requests of proposed acquisitions which are below both EU and national thresholds.1

These are only the second and third referrals of cases below the EU and national notification thresholds that have been accepted by the EC, but their emergence within a few days of each other and the markets they relate to could indicate that they are harbingers of more referral cases to come. Concurrently, in March 2023, the EU’s General Court held that a national competition authority may examine a dominant player’s acquisition of its competitor under the abuse of dominance rules, even if the transaction was originally notified and approved by a competent competition authority, giving regulators another avenue to review transactions.

The combination of the EC’s increasingly ambitious use of the referral mechanism and the General Court’s endorsement of the innovative use of abuse of dominance rules to review acquisitions has reduced legal certainty and increased the complexity of antitrust risk assessments for parties contemplating a transaction. As a result, all companies must consider carefully the merger control implications of their M&A strategy, even if the risks remain low for the majority of below-thresholds deals.

(i) EU Merger Regulation and Article 22

The EU’s Merger Regulation (EUMR)2 has had a profound effect on the ex ante protection of competition, giving the EC the power to review and block concentrations (mergers, acquisitions, or joint ventures) that have a community-wide dimension, and that would reduce competition within the EU’s internal market. The EUMR delineates the exact jurisdiction of the EC by including objective, turnover-based thresholds that a transaction must meet for the EC to have jurisdiction over it. The EC’s jurisdiction is exclusive, meaning that concentrations meeting these turnover thresholds are not to be assessed by individual Member States. This ‘one-stop shop’ approach has proven valuable for cross-border businesses, reducing their administrative burden and providing legal certainty through the need to secure a clearance decision from only a single authority, thus avoiding the risk of disparate outcomes.

At the same time, Article 22 of the EUMR provides a referral mechanism through which Member States can request the EC to examine any concentration that does not meet the EUMR’s turnover thresholds, but that still affects trade between Member States and threatens to significantly affect competition within the territory of the Member States making the request. A referral may be made even if the Member States’ jurisdictional thresholds are not met and can, in theory, be made by just a single Member State. Crucially, a referral is possible even after a transaction has been implemented, although the EC has indicated that it will generally not accept a referral request if it is made more than six months after a deal has closed and the closing has been publicly disclosed.

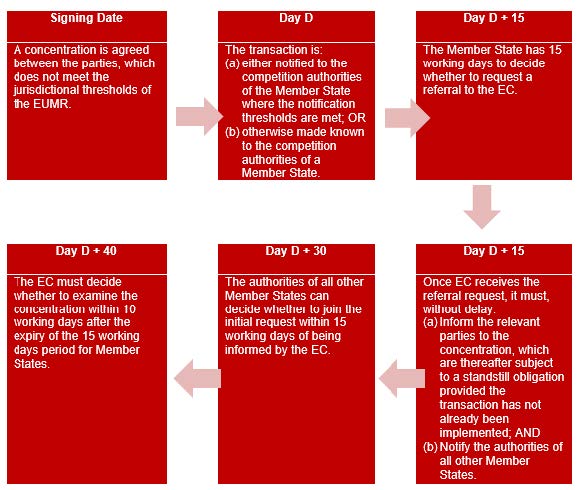

Under the referral system, Member States have 15 working days from the date on which the concentration was notified to them or, if no notification is required, “otherwise made known to them”, to decide whether to make a referral request to the EC. For a non-notified transaction to be considered made known to a national authority, the authority must have received sufficient information to preliminarily assess whether the criteria for a referral are met. Unfortunately, the EC’s guidance does not clarify what this entails and does not indicate the required information to be shared with national authorities. In practice, this may entail a ‘mini-notification’ to the national authorities of the most relevant Member States, containing similar information to formal notifications for transactions that meet the jurisdictional thresholds of those Member States. This is an unfortunate development, increasing uncertainty and exacerbating the legal and administrative burden for businesses that need to consider whether to contact any national authorities with mini-notifications and, if so, which ones.

Once a referral request has been made, the EC will inform the relevant parties to the concentration, which are thereafter subject to a standstill obligation, provided the concentration has not been already implemented. This prevents them from closing the concentration until clearance is received. The EC will also inform the authorities of all other Member States, which have 15 working days to decide if they want to join the initial referral request. Upon the expiry of this deadline, the EC has 10 working days to determine whether it will accept the referral request, and if it does so, the Member States no longer have jurisdiction to review the case.

Figure: Timeline of Article 22 referral mechanism

This quick succession of referral acceptances in August 2023 was a marked shift from the EC’s earlier approach, during which it discouraged Member States from making such referrals through its initial 2005 guidance on case referrals.3 In its 2005 guidance, the EC stressed that referrals are a derogation from the general rules whose use must be limited in light of the importance of the legal certainty that comes from the quantitative thresholds.

This guidance was updated on 31 March 2021,4 with the EC confirming its aspiration to use Article 22 referrals to capture so-called ‘killer acquisitions’ involving targets that currently have limited or even no turnover, but which may have a significant role in the market in the future, especially in the digital and pharmaceutical sectors. Such transactions often involve start-ups or recent market entrants with substantial innovation capabilities, which could render them an important competitive force in the future. The EC wants to preserve the opportunity for such competitive forces to arise, and its updated guidance on the referral mechanism reflects its intention to regulate whether such killer acquisitions can go ahead and under which conditions. To that effect, and following the EC’s updated guidance, on 19 April 2021, the EC accepted the first referral of a transaction that was below the turnover thresholds of both the EC and the referring Member States, and which, in line with the sectors identified in the EC’s updated guidance, involved the pharmaceutical sector.5

(ii) Lessons from Illumina/Grail

Illumina’s proposed acquisition of Grail has become a seminal case in the EC’s merger control practice and case law. The proposed acquisition of Grail by Illumina did not meet the notification thresholds of either the EU or any Member State and, accordingly, was not notified to any of them. Following a third-party complaint about this transaction, the EC informed Member States of the deal and invited them to submit a referral request about the transaction. Upon receipt of the referral request from the French competition authority, and in line with its obligations under the EUMR, the EC promptly notified the merging parties of the referral request, while also reminding them of the standstill obligation. Three more Member States, as well as Iceland and Norway,6 joined the initial request, and the EC accepted jurisdiction over the proposed transaction, despite it not meeting the notification thresholds of any Member State.

Illumina lodged an appeal against the EC’s decision to accept the referral request in which it mainly argued that the EUMR referral system could not be applied to mergers falling below the national thresholds of the referring Member States. The General Court considered the literal, historical, contextual, and teleological interpretation of the relevant rules and found that Article 22 of the EUMR can give the EC jurisdiction to review mergers even when they do not meet the national notification thresholds of any Member State.7 The General Court noted that the referral mechanism is intended to remedy the deficiencies of the turnover threshold-based system, which is not capable of covering all transactions that merit examination at the European level. Therefore, the General Court concluded that limiting the scope of the referral mechanism to transactions that meet national turnover thresholds would prevent merger control rules from achieving their objective of controlling transactions that are likely to significantly impede effective competition in the internal market.

The General Court added that the substantive requirements for the EC to accept a referral request and the time limits involved in this process preserve legal certainty, but businesses and legal practitioners have reacted with skepticism to this argument. Many commentators have remarked that the application of these time limits may prove contentious, especially when no formal notification is required due to the deal not meeting the jurisdictional thresholds of the referring Member State. The lack of a formal notification means that there is no clear starting date for the 15 working-days deadline during which Member States need to decide whether to request a referral of a particular case to the EC. Even if an acquirer informally approaches the competition authorities of a Member State to make a proposed acquisition known to them, the wording of the EC’s guidance means that national authorities have wide discretion as to when they can consider that a transaction has been made known to them, since they can claim that they did not have sufficient information to carry out their assessment of whether a referral request is needed.

As such, parties now face a dilemma: Should they approach national authorities to inform them of proposed below-thresholds acquisitions and start the ‘referral clock’ or should they avoid raising the profile of such deals in the hope that they can implement the deal before any authority takes issue of it, but risk a referral being made after a deal’s implementation? The answer to this will inevitably depend on the characteristics of each case, and legal advice should be sought to assess the antitrust risks associated with each approach.

As regards the Illumina/Grail case, Illumina appealed the General Court’s judgment, and this appeal is still ongoing.8 In accordance with the EC’s directions, in June 2021, Illumina formally notified the transaction to the EC, which a month later opened an in-depth investigation (Phase 2 review) to assess its impact in the relevant market.9 During the EC’s Phase 2 review of this transaction, and despite the standstill obligation being in force at the time, Illumina publicly announced that it had completed the acquisition of Grail, leading to a separate gun-jumping investigation and, eventually, a €432 million fine for breaching the EU merger control rules.10 The transaction itself was blocked by the EC, which found that the concentration would stifle innovation and reduce choice in the relevant market,11 leading the EC to issue a divestment order against Illumina on 12 October 2023.12 A divestment order is akin to undoing the transaction and returning the competitive situation to what it was prior to the merger’s completion. Illumina is currently appealing both the gun-jumping finding and the merger prohibition decision and plans to appeal against the divestment order as well.

(iii) Recent below-thresholds referrals

Despite the General Court’s judgment in the Illumina case being in favor of the EC’s approach, it took more than a year for the EC to accept any new referrals of below-thresholds transactions. Then, in mid-August 2023, the EC announced in quick succession that it had accepted the referral requests of several Member States regarding two separate cases.

The first referral would lead to the combination of two of the main suppliers of vehicle-to-everything semiconductors.13 Interestingly, the EC informed the Member States about this transaction on its own initiative and invited them to make the referral requests,14 illustrating the EC’s desire to use the referral tool to examine mergers that would otherwise escape its review. Seven Member States accepted the EC’s invitation by submitting initial referral requests to the EC, with eight more Member States joining the request at the later stage.

In contrast, the second referral arose at the initiative of just two Member States, demonstrating that there is no minimum number of referring Member States required for the EC to accept a request. This referral related to the proposed acquisition of Nasdaq Power by EEX,15 and it relates to the market for the provision of services facilitating the on-exchange trading and subsequent clearing of Nordic power contracts. If allowed, this merger would result in the combination of the only two providers of these services.

Both referrals relate to niche markets with high-entry barriers in the form of specific technological and technical know-how, and both entail the combination of the two largest players in their respective markets. Hence, these are useful indicators for companies to consider when assessing the risk of a referral request regarding their acquisitions. Moreover, the recently published Competition Merger Brief16 notes that the Article 22 referral mechanism aims to address the potential enforcement gaps in relation to “green” killer acquisitions of targets carrying out green innovation, giving further indications as to the sectors where more referrals may arise.

(iv) Towercast judgment and the risk of ex post investigations of mergers

The General Court’s Towercast judgment17 has added another arrow to the regulator’s merger control quiver. This case related to Towercast’s complaint that the acquisition of one of its competitors by the largest player in the French digital terrestrial television broadcasting services market amounted to an abuse of a dominant position. This acquisition was below the jurisdictional thresholds set out in the French merger control law, and consequently it was not notified to the French competition authority.

Since the acquisition did not meet the French jurisdictional thresholds, the French competition authority refused to investigate it further. Towercast appealed this decision to the French Court of Appeals, which submitted a request to the General Court for a preliminary ruling regarding the potential use of abuse of dominance rules to investigate a transaction. The General Court confirmed that below-thresholds transactions may be examined by national competition authorities after their implementation under the rules regarding abuse of dominance.

Accordingly, an acquisition itself may constitute abusive conduct if it substantially impedes competition in the market where the target is active and the acquirer is already dominant in that same market. This won’t arise simply because the dominant company’s position has been strengthened. Instead, it requires that as a result of the acquisition, the behaviour of all of the dominant company’s remaining competitors must be dependent upon the dominant undertaking, such as where a change in the prices of the dominant undertaking would have to be mirrored by its competitors.

Alarmingly, the General Court did not rule out the possibility of a double assessment of an acquisition under both merger control rules (ex ante) and abuse of dominance rules (ex post). Therefore, even transactions that meet the relevant jurisdictional thresholds and are cleared by the competition authorities may subsequently be subject to an abuse of dominance investigation. However, the General Court’s judgment did not give any indication regarding under which circumstances this could occur, and it remains to be seen whether, in practice, national competition authorities would proceed with such contradictory actions.

The General Court in the Towercast judgment also refused to apply a time limit to the power of national competition authorities to review concentrations under abuse of dominance rules, increasing the uncertainty as to when competition concerns regarding a transaction can cease.

This alternative method to review a merger is limited solely to cases where the acquirer is already dominant in the relevant market, hence most transactions are unlikely to be affected by this decision. Additionally, the complexity of abuse of dominance cases and the high threshold for anticompetitive effects required to claim that an acquisition itself constitutes an abuse of dominance may discourage competition authorities from pursuing such claims. The Belgian competition authority was the first to cite this judgment when it opened an investigation into Proximus’ takeover of a competitor in March 2023,18 and more guidance regarding the application of the Towercast judgment is expected as the Proximus case proceeds.

(v) Impact on transactions and business

These developments substantially increase uncertainty in deal-making – especially in the tech and pharmaceutical sectors, but increasingly in other sectors too – requiring that transaction timelines and documentation reflect the increased risk of a referral to the EC being accepted, even after closing. Simultaneously, any acquirer with a dominant position must also keep in mind the risk of an ex post evaluation of its transaction under the abuse of dominance rules, with no time limit in place for when such an evaluation may occur.

Proactive engagement with the most relevant national competition authorities may be helpful for parties wishing to gauge the referral appetite of the authorities, though this may also increase the risk of a referral by bringing a transaction into the spotlight. Additionally, it is advisable that the parties unambiguously announce the closing of their transaction. This would create a clear starting point for the six-month post-closing time limit that the EC has indicated as its usual temporal limit to accept a referral request. However, both the EC’s updated guidance and the Towercast judgment keep the potential for a review of a transaction open beyond the six-month period, leaving no definitive endpoint for a transaction to be considered irreversibly safe from an antitrust perspective.

Nonetheless, it is important to remember that most below-thresholds transactions will not attract this level of scrutiny. Only a few referral requests occur each year – as evidenced by the EC’s reluctance to open the floodgates – with only seven referral requests having been made since the 2021 updated guidance and only three of those relating to transactions below national thresholds.19 Additionally, the scope for an ex post evaluation of a merger under the abuse of dominance rules is limited, only covering more exceptional circumstances. Ultimately, every transaction is unique, and legal advice should be sought to ensure that the most appropriate steps are taken in each individual case.

- M.11212 Qualcomm/Autotalks, Referral accepted on 17 August 2023; and M.11241 EEX/Nasdaq Power, Referral accepted on 18 August 2023.

- Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 of 20 January 2004 on the control of concentrations between undertakings.

- Commission Notice on Case Referral in respect of concentrations (2005/C 56/02).

- Communication from the Commission Guidance on the application of the referral mechanism set out in Article 22 of the Merger Regulation to certain categories of cases (2021/C 113/01).

- M.10188 Illumina/Grail, Referral accepted on 19 April 2021.

- According to Article 6(3) of Protocol 24 of the EEA Agreement, EFTA countries may join a request for referral made by a Member State under Article 22 of EUMR if the concentration affects trade between one or more Member countries and one or more EFTA countries and threatens to significantly affect competition within the territory of the ETFA country or countries joining the request.

- Case T-227/21, Illumina, Inc. v. European Commission, 13 July 2022, ECLI:EU:T:2022:447.

- C-611/22 P – Illumina v. Commission.

- M.10188 Illumina/Grail, Decision to open in-depth investigation of 22 July 2022.

- M.10483 Illumina/Grail (Article 14 procedure), Decision of 12 July 2023.

- M.10188 Illumina/Grail, Prohibition decision of 6 September 2022.

- M.10939 Illumina/Grail (Restorative measures under Article 8(4)(a)), Decision of 12 October 2023.

- These are chipsets that enable vehicles to communicate directly with each other and their surrounding environment.

- In accordance with its powers under Article 22(5) of the EUMR.

- M.11241 EEX/Nasdaq Power, Referral accepted on 18 August 2023.

- Competition merger brief, Issue 2/2023 – September. Competition merger briefs are written by the staff of the Competition Directorate-General and provide background to policy discussions. They represent the writers’ view on the matter and do not bind the EC in any way.

- Case C-449/21, Towercast SASU c. Autorité de la concurrence, 16 March 2023, ECLI:EU:C:2023:207.

- Belgian competition authority, Press Release nr. 10/2023, 22 March 2023.

- European Commission, Competition Policy, Statistics on Mergers cases 21 September 1990 to 31 August 2023. Four out of the seven referrals accepted since 2021 met the national thresholds of at least one referring Member State.

In-depth 2023-244